INTERNATIONAL POLITICS

Tinubu, Matter Don Pass be Careful

Published

3 months agoon

By

Editor

By Lasisi Olagunju

The last premier of the Western Region, Chief Samuel Ladoke Akintola, asked his guest what the town was saying. The guest told him the town was solidly behind him. The guest backed his claim with a cassette which he said contained the adulation with which the people of Ibadan welcomed every step so far taken by Chief Akintola. The premier listened to the cassette and brightened up. He thanked the guest, Chief A.M.A. Akinloye, as he took his exit. Akintola’s young confidant and aide, Adewale Kazeem, walked in. The premier told him of Akinloye’s good news and gave him the cassette to listen to. Adewale listened to the cassette, sighed and was downcast. The premier looked at the worried face of Adewale Kazeem and asked why. “The town is not good,” he told Chief Akintola, and added that the content of the cassette was not a true reflection of what the town was saying about the premier and his government. A shocked Akintola intoned “ta l’a á wàá gbàgbó báyìí (who do we believe now)?” The young man told the premier: “You had better believe me, Baba.”

The above happened sometime in 1964. A year later, the problem multiplied for Chief Akintola who became increasingly troubled, his hands unsteady; “he could no longer write his signature on a straight line.” One day, he was advised by the same aide, Adewale Kazeem, to resign his post as premier and end the raging crisis in the region. Akintola’s response was: “Adewale, ó ti bó; ikú ló má a gb’èyìn eléyìí (Adewale, it is too late. It is death that will end all this).” The above details are on pages 161 and 172 of the book ‘SLA Akintola in the Eyes of History: A Biography and Postscript’. The book, published in 2017, was written by a former member of the House of Representatives, Hon. Femi Kehinde. The author did not put those conversations in the book as hearsay. He heard them directly from Adewale Kazeem who rose in life to become a well-respected oba in Osun State.

At 5.50pm on 6 August, 1962, Chief Obafemi Awolowo left his place for the residence of the Prime Minister, Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, for a 6pm appointment. It was at the height of the political crisis of the early 1960s. Awo arrived at Balewa’s 8 Lodge on the dot and wasted no time opening their discussion. He asked Balewa: “Are you sure in your mind that this crisis will end well for all of us and for Nigeria?” Chief Awolowo said “Balewa replied in a low, solemn voice that he was sure it would not end well…” (See Awolowo’s ‘Adventures in Power’, Book Two, page 249). And, did it end well? There is no point answering that question. We all know how it ended. Today, there is a new fire on the mountain. Things are bad; very bad. Paris-born Nigerian singer, Bukola Elemide (Asa) sings: “There is fire on the mountain/ And nobody seems to be on the run…” The first time we heard a cry of fire and fear in our politics was in the Western House of Assembly in 1962. Since then, the mountain of Nigeria has been badly scarred by political bush-burners. A fresh blaze is balding the skull of the poor today and the consequences cannot be imagined.

There are consequences for everything anyone does or does not do. Even the words that I use here will have consequences. Ethnic and business ‘friends’ of the president will abuse me like they’ve always done to poets who refuse to do palace clowning. They forget that I am a child of the farm; I walk the furrows, not the ridge. I am beyond their shot. Authored by researchers Iain McLean and Jennifer Nou, a piece appeared in the October 2006 edition of the British Journal of Political Science. And the title? ‘Why should we be beggars with the ballot in our hand?’ That is the question we dare not ask here without them saying we should bring our heads. They say the president is our brother who cannot do wrong. They forget that we were not taught in Yoruba land to merely chase away the fox and pamper the cocky bumbling hen. We were taught to give justice to fox and then to hen – one after the other. How is keeping quiet when the ‘war’ is all around us going to help “our brother”?

The hunger that is in town today is more serious than the hunger that made Sango burn down a whole town. Yet, our leader appears not worried. He is not scared. It is business as usual. Why are we not fearing the consequences of our misbehaviour? A journalist recalled that sometime in 1965, Prime Minister Balewa was at the airport in Ikeja and was asked what he was doing to quench the fire in the Western Region. The big man looked around and declared that “Ikeja is part of the West, I can’t see any fire burning.” Truly, he was kept busy with positive assurances by flightless birds around him. He lived in denial, or in self-deception, he ignored the firestorm. The fire he refused to see grew uncontrollably wild; it became a blaze so much that when the cock crowed at dawn on January 15, 1966, it was too late for the head of the Nigerian government to save even himself.

There were protests in parts of the country last week by hungry Nigerians. But President Bola Tinubu’s trusted people said the protests were unreal; they said the president’s policies are good and popular with the people. They are telling the president that the hungry are not very hungry. They said it was the opposition playing politics, inciting the poor against the state. I saw Lagbaja, the mystery musician, from a distance at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, on Friday. I tried unsuccessfully to reach him and get him to sing: ‘Mo sorry fun gbogbo yin’ to those telling the naked president that his garment is beautiful. The ‘sorry’ is more for Tinubu. He is the one chosen and crowned to rule; and he is the one whose tenure is being measured by mass suffering, mass hunger, mass kidnapping. He is the one being scaffolded from the ugliness of the street. Tinubu is an elder. Should it be difficult for him to know the next line of action when a load is too heavy for the ground to carry and is too heavy for the rafters? We say in Yoruba land that when the going gets tough and life faces you, shoot at it; if it backs you, shoot it. When you are alone, reconsider your stand.

Did President Tinubu read Segun Adeniyi of Thisday last week? The columnist asked him to go and watch again the Yoruba mainframe play, Saworoide. If you are not Yoruba, look for the plot summary of that play, it should be online. Read it. It should tell what the warning is all about. They are all prophets – the warners. Did the president read Abimbola Adelakun of The Punch last Thursday? She warned that “things are getting out of hand.” Did Tinubu read Tunde Odesola of the same newspaper the following day? He wrote that in Tinubu’s Nigeria, “the poor can’t inhale, the rich can’t exhale.” Farooq Kperogi of Saturday Tribune has written twice (last week and the week before) on hunger and anger in the land. He warned Tinubu two days ago not to see himself as Buhari who misruled big time but escaped the whips of consequences. Festus Adedayo yesterday in the Sunday Tribune likened today’s Nigeria to ravaged Ijaiye, a defeated community of hopelessness. I, particularly, find very apt Adedayo’s reading of today’s suffering as Kurunmi’s war-ravaged Ijaiye of 1860/61. In 2024 Nigeria, respectable people beg to eat; mothers sell one child to feed another. It is tragic. Bola Bolawole’s offering drew from French and Russian histories of social and political tragedy. I do not know what Suyi Ayodele of the Nigerian Tribune is cooking for tomorrow, Tuesday. I will be surprised if Tinubu’s ‘friends’ have not reported these warners to him as his enemies. That is how we are being governed.

The naira is ruined, the kitchen is on fire. We thought the regime of Muhammadu Buhari was the last leg of Nigeria’s relay race of tragedy. Now, it is clear he was actually the first leg in a race that won’t end soon. Tinubu took the baton from his game-mate and said his wand is made of hope in renewed bottles. His first eight months have proved that it is not true that the child does not die at the hands of the circumciser. This is better said in Yoruba – àsé iró ni wípé omo kìí kú lówó oní’kolà! This one is dying – or is dead. Before the president’s very eyes, the country has become a vast camp for stranded people; a nation of displaced people who live on food rations. The people now ask who is going to be their helper. Legendary Ilorin musician, Odolaye Aremu, at a moment of anomie as this, lamented that the one we said we should run to for safety is urging us to run even far away from where he is (eni tí a ní k’á lo sá bá, ó tún ní k’á máa sá lo).

Cluelessness is a physician treating leprosy with drugs made for eczema. Who told the president that opening the federal silos is the solution to a bag of rice selling for N70,000? It was N7,000 nine years ago. The protesting people from the north and in the south are not saying there is no food in the market. There is no scarcity of foodstuffs. It is not a demand and supply problem. There is food in the market, but the food in the market is priced beyond the earnings of the people. That is the issue, the problem, and it cannot be solved with handouts from grain reserves. It can only be solved with a magic that will shrink the price of foodstuffs to a size within the financial capacity of the poor.

Some say it is age that ails Tinubu making him unfelt in this season of pain. But, he won’t be the first old man to be king. There was a prince in Ofa who owned neither calabash nor plate (kò ní’gbá, kò l’áwo). But he had a large piece of cloth as his only item of value. He did not use it; it was too unuseful to the poor old man who would rather lend it for a fee to others for use on their special outings. The man’s condition remained critical, his poverty unremitting. He prepared himself and went to an elder for consultation. He sought counsel on what he could do so that he might gain importance. He was told to give up the large piece of cloth, sit back and watch. He did as he was told and soon after that sacrifice, the king of Ofa died and the people of Ofa made the poor old man king. They said among themselves that “this one will not be long before he dies and another will take his place.” But the old man became king and refused to die. Instead of dying, he became increasingly robust, younger and stronger. Life and living in Ofa became good and pleasant as well. The poor became prosperous and the rich richer. The people of Ofa fell in love with their king; they no longer wanted him to die. He reigned long and well. At the end of his journey, the departing king was satisfied that he had good tidings to take to his alásekù – those who reigned without destroying the crown, the ones who passed the stool to him for him to pass to others. This Ofa story belongs in the grove of the wise; it is deeper than I have told it. Its code is with the elders.

All who are favoured are counselled to take it easy with life. They should cast away the garment of greed, of hubris and of lust for the self. If they care, they can take counsel from these lines from the ancestral scroll: “Do not run the world in haste. Let us not hold on to the rope of wealth impatiently. What should be treated with mature judgment should not be treated in a fit of temper. Whenever we arrive at a cool place, let us rest sufficiently well and give prolonged attention to the future; let us give due regard to the consequences of things. We should do all these because of the day of our sleeping, our end (Má fi wàrà wàrà s’ayé, K’á má fi wàrà wàrà rò m’ókùn orò. Ohun a bâ fi s’àgbà, K’á má fi sè’bínú. Bí a bá dé’bi t’ó tútù, K’á simi simi, K’á wo’wájú ojó lo títí; K’á tún bò wá r’èhìn òràn wò; Nítorí àtisùn ara eni ni).

Tinubu’s salvation lies with his orí inú– his inner head. That is the priest he should consult. It is what he should go and ask for the way. His reign is painful.

Originally published in the Nigerian Tribune on Monday, 12 February, 2024

You may like

By Steve Osuji

CRISIS DEEPENS: President Bola Tinubu has announced a no-confidence vote on himself, unknown to him. He inadvertently admitted that he is unable to do the job and that his administration is in crisis when he inaugurated two hurriedly cobbled up, new-fangled economic committees to run things and revive economy. The first one is a 31-member Presidential Economic Coordination Council (PECC), while the other is a 14-man Economic Management Team Emergency Task Force, code-named (EET).

If Nigerians noticed the move by Tinubu, they didn’t seem to give a damn. Many had long given up on the Tinubu presidency anyway and they have switched off its activities. They have come to the eerie realization that Tinubu is not the man to get Nigeria out of the morass of poverty and underdevelopment, so many have long moved on with their lives, leaving the man to continue with his extended blundering and shadow-boxing.

The teams are made up of the usual culprits: the jaded Dangote-Otedola-Elumelu circle; the Bismarck Rewane-Doyin Salami-Soludo celebrity-economists and the same raucous crowd of governors and ministers. The same motley crowd of people who brought Nigeria to her current tragic destination has been gathered again!

Apparently, Bola Tinubu forgot he had just last February, assembled the Dangote-Elumelu hawks as his Economic Advisory Council members. Scratch! That was just another presidential blunder out of so many. Now PECC and EET are Tinubu’s NEW DEAL. Call it “peck and eat” if you like but that’s the new buzz in Aso Rock. But for discerning minds, this is a clear sign that crisis has deepen in Tinubu’s administration.

SELF-INDICTMENT: But which serious president sets up a new economic management task force after 10 months in office? What about its cabinet? Has it been rid of the failed ministers and aides whose apparent failure warranted a side team like this? What has the new government been doing in office all this while? What about the election manifesto and the president’s economic vision Could it be that all these have been forgotten in 10 months to the point that outsiders are needed to give direction and “revive” the economy?

Now some ministers and state governors have been co-opted into this new TASK FORCE. They are mandated to meet twice a week in Abuja for the next six months. So what happens to the governors’ duties back home? What about the ministers’ core assignments? All of this seems quite weird right now. The simple message here is that the president has lost focus and direction. Vision, if any, has failed him. The presidency is weak and puny nobody is holding forth in case the president falters.

BLANK SCORECARD: Now almost one year in office, no scorecard, nothing to report. All the positive indictors the president met upon inauguration have all crashed to near zero. Even the deposits in the blame banks have been exhausted – there’s nobody to blame anymore!

LOW CAPACITY, LOW ENERGY: This column has warned right before election that Tinubu hasn’t the requisite mental and physical capacities to lead Nigeria. As can be seen by all, President Tinubu has not managed to tackle any of the fundamentals of the economy and the polity; the very basic expectations in governance are not being attended to. For instance, the corruption monster rages on afield, with Tinubu seemingly not interested in caging it. Official graft has therefore worsened under his watch. About N21 billion budgeted for his Chief of Staff as against N500m for the last occupant of that office has become the compass for graft in Tinubu’s Nigeria. Today, the police is on a manhunt for the investigative journalist exposing filthy Customs men while the rogues in grey uniform are overlooked. The president personally ballooned the cost of governance by forming a large, lumbering cabinet and showering them with exquisite SUVs, among other pecks.

Insecurity is at its worst with no fresh ideas to tackle it. The country is in semi-darkness as power generation and distribution is at near-zero levels. Importation goes on at a massive scale, productive capacity has dwindled further and living standard of Nigerians is at the lowest ebb now. There’s hardly anything to commend the Tinubu administration so far.

WHO WILL RESCUE THE SITUATION: As Nigeria’s socioeconomic crises deepen, and the president’s handicaps can no longer be concealed, who will rescue the polity? All the stress signs are there; the fault lines are all too visible to be ignored anymore. Recently, we have seen civilians brazenly butchering officers and men of the Army and the army brutishly exacting reprisals almost uncontrolled. We see the escape from Nigeria, of the Binance executive who had been invited to Nigeria and then slammed into detention. That a foreigner could slither out of the hands of security personnel and slip out through Nigeria’s borders, suggests unspeakable ills about the country. The other day, so-called MINING GUARDS in their thousands, were suddenly ‘manufactured’ – uniforms, boots, arms and all. They are conjured into existence ostensibly to guard the mines. Which mines? Whose mines? How much do the mines contribute to the federation account? Are we using taxpayer’s money to fund an army to protect largely private and illicit mines? Why are we committing harakiri by throwing more armed men into our unmanned spaces? Even the Nigerian Navy has been unable to protect Nigeria’s oil wells! The Mining Guard is yet another symptom of an insipient loss of control by the President.

Finally, for the first time in a long while, an editor, Segun Olatunji, was abducted from his home in Lagos. For two weeks, no one knew his whereabouts and no arm of the military cum security agencies owned up to picking him in such bandits-style operation. It took the intervention of foreign media and human rights bodies for the Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA) to own up they abducted him, and eventually release him. Not one charge was brought against him.

Not even under the military junta were editors kidnapped by security agencies in this manner. The point is that the so-called democrat-president is losing patient with the media. There shall be many more abductions and media mugging in the coming days. When a government fails, it kicks the media’s ass for reporting the failure; that’s the historical pattern!

Things will go from bad to worse and government would respond in more undemocratic and authoritarian ways. Lastly, it’s unlikely that Dangote and Co can rescue the dying Tinubu presidency? These are fortune-hunters craving the next billion dollars to shore up their egos. To mitigate the looming crisis, Tinubu must quickly reshuffle his cabinet that is currently filled with dead woods and rogues. Many of them are too big for their shoes and they are not given to the rigors of work.

In fact, Tinubu must as a matter of urgency, fortify the presidency by changing his chief of staff to a Raji Fashola kind. As it is, the hub of the presidency is its weakest link.

Steve Osuji writes from Lagos. He can be reached via: steve.osuji@gmail.com

#voiceofreason

Feedback: steve.osuji@gmail.com

By Dr Chidi Amuta

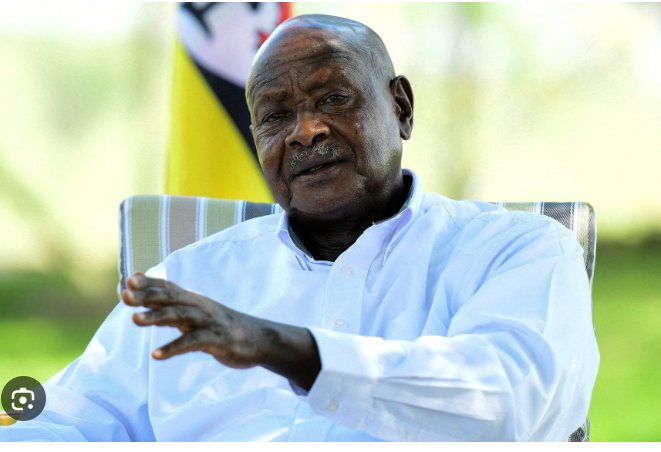

Within the diverse pantheon of African rulership, something curious is emerging. In many ways, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda is fast emerging as a model of the transformation of democracy into authoritarianism in Africa. While Museveni has retained his nationalist streak in the fight against the global LGBTQ epidemic as well as his isolated battles against Western multinational exploitation and blackmail, his practice of democracy and adherence to the rule of law would disappoint pundits of African democratic enlightenment.

He has repressed basic freedoms, violated the rights of his political opponents, bludgeoned opposition political figures and jailed those who disagree with him. He has enthroned what is easily a personality cult of leadership that is easily a combination of draconian military dictatorship and crass authoritarianism. That is not strange in a continent that has produced the likes of Nguema, the Bongos and Paul Biya.

In addition, Museveni now displays some of the worst excesses of Africa’s famed authoritarianism, dictatorial indulgence and the dizzy materialism of its leadership. For instance, the president is reported to travel around with an interminable motorcade that includes a luxury airconditioned toilet. Worse for Uganda’s democracy are the recent stories of Museveni’s manouvres towards self succession. Specifically, he has appointed his son as Chief of the army, a move which many observers of Uganda see as a pointer to his succession plan.

For me, the unfolding Museveni authoritarianism is a classic instance of the transformation of African leaders from revolutionary nationalists to authoritarian emperors. I once met and spoke with the early Museveni. He had emerged from a bush war as a liberator and valiant popular soldier that was heralded into Kampala as a liberators. He came to mend a broken nation from the locust ears of Idi Amin and Milton Obote.

The Museveni that I sat and conversed with in the early 1990s was a committed socialist. He was an African nationalist. He was a social democratic politician with a strong social science background. His primary constituency was the people most of whom fired his liberation movement in the countryside. We exchanged ideas freely on the thoughts of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Frantz Fanon, Walter Rodney and Amilcar Cabral among others.

As the Chairman of the Editorial Board of the new Daily Times under Yemi Ogunbiyi, I initiated and conducted a one on one interview with Yoweri Museveni in his early days after the overthrow of Obote with the backdrop of the Idi Amin carnage. What follows is both a travelogue and a reminiscence of the Museveni before now. Is it the same Museveni or are there two Musevenis?

In 1991, I scheduled a trip was to Kampala to interview Yoweri Museveni. I travelled alone through Addis Ababa and Nairobi. In those days, inter African flight connections were a nightmare of stops and delayed connections. I arrived Kampala and found my long standing friend, Dr. Manfred Nwogwugwu, a demographer who was based in Kampala as head of the United Nations Population Commission. We had been together at Ife where he and his lovely wife, Ngozi, hosted me for the weeks it took me to find my own accommodation as an apprentice academic at Ife. He took me on a tourist trip around Kampala. The city was broken and bore fresh bullet holes and bomb craters, the marks of war. From Biafra, I knew this ugly face well enough. Kampala had just been liberated by Museveni’s forces after ousting Milton Obote and remnants of Idi Amin.

I knew as a background that Mr. Museveni had been helped in his guerilla campaign by both M.K.O Abiola and General Ibrahim Babangida, then president of Nigeria. He therefore had a very favourable disposition towards Nigeria. He was also quite influential with African leaders from whom Nigeria was seeking support as General Obasanjo was lobbying to become United Nations Secretary General when it was deemed to be the turn of Africa. As a matter of fact, I was joined at the Museveni interview by Obasanjo’s media point man, Mr. Ad Obe Obe, who had come to interview Museveni as part of the Obasanjo campaign.

Museveni’s Press Secretary, a pleasant but tough woman called Hope Kakwenzire, kept in touch while I waited in Kampala for my appointment. She was sure the interview would hold but wanted to secure a free slot on the President’s choked schedule. She promised to call me at short notice to head for the venue.

When she eventually called, it turned out that the interview venue had just been switched from the Kampala State House to a government guest house in Entebbe, close to the airport and by the banks of Lake Victoria. Entebbe brought back memories of the famous Mossad raid to free hostages of a Palestinian hijack of an Israaeli plane. At the appointed time, I was picked up from my friend’s residence. As we headed for Entebbe, memories of the dramatic Israeli commando rescue of airline hostages at Entebbe during the Amin days kept flashing through my mind. When I arrived Entebbe airport on my way in, I was shown the warehouse where the hostages were kept ahead of their dramatic rescue. The rescue had made world headlines in those days. It reinforced Israel’s military prowess and the intelligence dexterity and detailed planning of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) but the operational dexterity and intelligence excellence of Mossad in particular.

We arrived a nondescript white bungalow tucked amidst trees and vegetation. It was a colonial type sprawling white bungalow. The entrance gate was a long drive from the building itself. When your car is cleared through the first gate, you drive along a bushy drive way towards the building. The first gate has normal military sentry who already know you are expected. As you drive along the bushy driveway, some surprise awaits you. Suddenly some small figures in full combat gear dart onto the drive way and wave your vehicle to a sudden stop at gun point. They are too young and too small to be regular soldiers. But their moves are rather professional and smart. They are ‘child soldiers’ or rather ‘baby soldiers’ who had fought alongside Museveni’s liberation forces in the bush war that led to the freedom of Uganda. No emotions, No niceties. They screen the vehicle scrupulously for explosives. These small men have apparently been trained to trust no one. They ignore the escort and Press Secretary both of whom are familiar faces. They insist I answer their questions for myself. I explain I have an interview appointment with the President. They briefly return to their tent at the wayside and briefly confer by radio communication.

They wave us through to the building. I am taken through a rather unassuming hallway and a colonial looking living room and dining areas that opens into a simple sit out at the back of the building. The sit out at the back of the building opens into a vast courtyard with well manicured green gardens. The extreme end of the green is Lake Victoria. At its banks, there are tents with simple garden chairs. The serenity of the location is striking. Even more chilling is the eerie silence of the location except for the flapping of the wings of flamingos and pelicans playing by the lakeside. I quickly framed it in my mind: “Conversations by Lake Victoria!”

Seated alone in one of the tents is President Yoweri Museveni, the new strongman of Uganda. His simplicity beleis hthe mystique of courage and valour that now define his reputation. He was a leading figure in Africa’s then latest mode of political ascension: the strong man who wages a guerilla movement in the countryside and marches from the forest into the city center of the capital after toppling an unpopular sitting dictator and his government with its demoralized army . After him, Joseph Kabilla of the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) and Charles Taylor of Liberia followed the same pathway of political ascension but with differing outcomes.

The man in the tent was dressed in a simple black suit. He welcomed me very casually and warmly. “Nigeria is a long way from here, I imagine!”, he said jovially as he ushered me to take a seat. As we settled down to exchange views, it turned out that our exchange would be more than an interview. It was more of a radical social science conversation.

We compared notes on the class struggle in Africa, the burden of the political elite far removed from the masses, the alienation of the rural masses, the working class in Africa’s imperialist inspired industrialization. Museveni was very knowledgeable and sharp. His intellectual exposure was impeccable. He knew a lot about Nigeria, about our cities and the structure and general disposition of our elite. He had very kind words about M.K.O Abiola and his commitment to African unity and liberation which he was supporting with his vast resources. In particular, he supported Abiola’s ongoing campaign for reparations from the West to Africa for the decades of pillage during the slave trade and the subsequent colonial expropriation and haemorrhage of resources.

I still managed to pierce through his armour of social science and dialectical materialist analysis to ask him a few worrying questions about Uganda and Africa’s political future. He was generally optimistic about the turnaround of Uganda after the devastation of war and the rampaging carnage of dictators.

He added that he was facing the tasks of reconciliation among Ugandans after decades of division and distrust just like Nigeria did after our own civil war. He invited me to return to Kampala a few months hence to witness what the will of a determined people can do towards post war reconstruction. He told me he was out to fix not only the broken landscape of the city but more importantly the destroyed lives of many poor Ugandans. When I mentioned what I had seen of the devastation of AIDS in the countryside, he nearly shed tears but sternly reassured me that he would contain the scourge of the epidemic by all means.

I left Museveni on a note of optimism on the prospects of Africa’s comeback after the days of the Mobutus, Amins, Obotes and Bokasas. Given my own left leaning ideas, I found Museveni a kindred spirit and an unusually enlightened and progressive African statesman. He questioned everything: African traditions, beliefs, the assumptions of African history, the political legacy of the colonialists and the neo colonial state. He discussed pathways to Africa’s future economic development and the urgent need to question and possibly jettison old development models being peddled by the West through the World Bank and the IMF.

That was Museveni back in 1990-91.

Dr. Amuta, a Nigerian journalist, intellectual and literary critic, was previously a senior lecturer in literature and communications at the universities of Ife and Port Harcourt.

INTERNATIONAL POLITICS

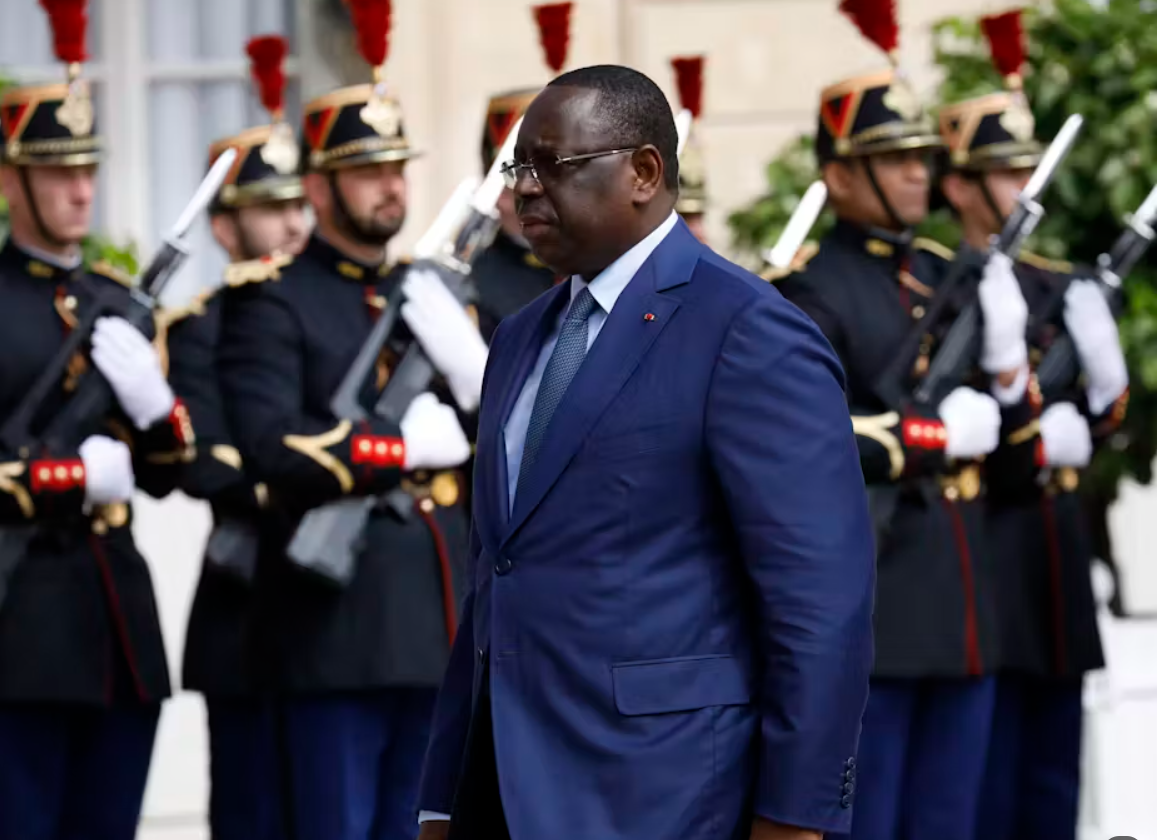

Senegal: Macky Sall’s Reputation is Dented, but the Former President did a Lot at Home and Abroad

Published

4 weeks agoon

April 1, 2024By

Editor

By Douglas Yates

Macky Sall’s legacy as Senegal’s president since 2012 became more complex in his last year in office. The year was so filled with transgressions that they appeared to have tarnished his reputation indelibly. For some months he gave the impression to his adversaries and critics that he had third-term ambitions – not uncommon in contemporary west African politics. A public outcry followed his decision on 3 February 2024 to postpone the polls that had originally been scheduled for three weeks later. Then his deputies in the national assembly voted unanimously to postpone the elections and prolong Sall’s term in office until December.

On 6 March, the country’s Constitutional Council ruled that the delay was unconstitutional and that the elections would have to be held before 6 April before April 2 rather, when Sall’s presidential term expires. In compliance, Sall slated Senegal’s election for 24 March. With that decision, the danger of an authoritarian drift in Senegal appears to have been averted. The time has therefore come for a more reasoned evaluation of his eight years in office.

I’ve been an observer of Senegalese politics since the late 1990s, doing democracy building for the US Information Agency’s Africa Regional Bureau, teaching African politics to graduate students in Paris, and commenting in the media on developments in Senegalese politics. Based on my experience, I would argue that Sall’s presidential terms have made some economic, domestic and international achievements worth remembering now, in these days of suspense and doubt. In my view the legacy of Macky Sall has been saved. Or at least that is how it appears.

What he leaves behind

Among his presidential legacies are major infrastructure projects, including airports, a better rail system and industrial parks. Senegal’s airports were in a deplorable condition when he came to office. The country had 20 airports, but only nine had paved runways. In their poor state, these airports did not attract the major international business flyers who could set up businesses and hire the country’s educated workforce or collaborate with its innovative entrepreneurs.

Blaise Diagne International Airport, named after the first black African elected to France’s parliament in 1914, opened in December 2017. The project, which was started in 2007 by his predecessor, Abdoulaye Wade, was completed by Sall. Located near the capital, Dakar, with easy access via a modern freeway, it has boosted passenger mobility and freight transport. The national airline, Air Senegal, is based here. It reaches more than 20 destinations in 18 countries.

Sall also built the country’s first regional express train, the Train Express Regional, an airport rail link that connects Dakar with a major new industrial park (also built during Sall’s tenure) and the Blaise Diagne International Airport. Sall also strengthened the regional airport hubs of the country. He spearheaded the reconstruction of five regional airports within Senegal. The Diamniadio Industrial Park, 30km east of Dakar, financed by loans from Eximbank China, was completed in 2023. The park is a flagship industrial project of Sall’s industrialisation strategy for Senegal.

The new park is positioned at the heart of a network of special economic zones, including Diass, Bargny, Sendou and Ndayane. Enterprises from multiple fields, including pharmaceuticals, electronic appliances and textiles, are setting up offices in the park, which is expected to manufacture high-quality products that meet local needs. The airports, trains and industrial parks are expected by Sall’s supporters to make a real contribution to Senegal’s transformation from post-colonial peanut exporter to import-substitution manufacturing hub.

In my view, what Sall leaves behind is substantial, particularly when compared with the highly controversial African Renaissance Monument of his predecessor Abdoulaye Wade. The 171-foot-tall bronze statue located on top of a hill towering over Dakar, built by a North Korean firm, has contributed little or no value to the country’s economy. Sall has also made some contributions to Senegal’s reputation abroad, positioning himself as a respected and influential player on the international stage. As president of the regional economic body Ecowas in 2015-2016, he made improving economic integration the focus of his term.

He also worked to build closer relations with other international organisations, including the G7, G20 and the African Union. While chairman of the AU from 2022 to 2023 he lobbied for inclusion of the African Union in the G20, complaining that South Africa was the continent’s only member of any economic forum of international importance.

In his address to the United Nations General Assembly, he championed the cause of the continent. There was no excuse, he said, for failing to ensure consistent African representation in the world’s key decision-making bodies. He emphasised the importance of increased funding from developed countries for climate adaptation initiatives in developing countries, particularly those in Africa.

Sall’s management of the COVID crisis, which reached Senegal in March 2020, was his first major test of leadership. Despite its limited resources, Senegal outperformed many wealthier countries in its COVID pandemic response, thanks to Sall’s leadership.

Contribution to Senegal’s democratic tradition

His important legacy will be his participation in the democratic tradition of Senegal. Firstly, he took on Abdoulaye Wade’s dynastic ambitions to name his son Karim Wade as the heir apparent. Sall then went on to respect his two-term limit on the presidency. This means he will soon hand power over to a successor, maintaining a unique and uninterrupted tradition of power transition in one of west Africa’s most stable democracies.

It hasn’t all been plain sailing. In recent years, the temptation of power seemed to have overwhelmed Sall. He started giving out troubling signs of his desire to remain in office beyond his constitutional mandate. Then, after testing the waters and finding public opinion was strongly opposed to his violating the limits that he himself had imposed while in the opposition to his predecessor, he declined to present himself for elections. Instead, he endorsed the candidacy of his then-prime minister Amadou Ba.

But this was followed by a series of arrests of his most vocal opponents, in particular the popular social media celebrity Ousmane Sonko. More than 350 protestors were arrested during demonstrations in March 2021 and June 2023. At least 23 died. Then came his last-minute presidential decree postponing the election earlier scheduled for 25 February.

This was followed by democracy protests and by violent police repression of urban protests, which resulted in civilian deaths. After protests, Sall made another extraordinary about-turn. He announced that he would respect the Constitutional Court decision, which denied him the right to prolong his presidential mandate and required that elections be held before 6 April. In doing so he preserved the system of checks and balances in Senegal. In addition, his decision to release Sonko and his other opponents from prison and grant them amnesty has preserved the space for democratic opposition and civil liberties.

Sall’s legacy as a voice of Africa may offer him a lateral promotion from the presidency of Senegal to the seat of some international organisation.

By Douglas Yates, Professor of Political Science , American Graduate School in Paris (AGS)

Courtesy: The Conversation

Promoting Halal Entrepreneurship Among Students: Opportunities and Challenges

Dangote, Air Peace and the Patriotism of Capital

EARTH DAY 2024: Packaging Is the Biggest Driver of Global Plastics Use

Topics

- AGRIBUSINESS & AGRICULTURE

- BUSINESS & ECONOMY

- DIGITAL ECONOMY & TECHNOLOGY

- EDITORIAL

- ENERGY

- EVENTS & ANNOUNCEMENTS

- HALAL ECONOMY

- HEALTH & EDUCATION

- IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

- INTERNATIONAL POLITICS

- ISLAMIC FINANCE & CAPITAL MARKETS

- KNOWLEDGE CENTRE, CULTURE & INTERVIEWS

- OBITUARY

- OPINION

- PROFILE

- PUBLICATIONS

- SPECIAL FEATURES/ECONOMIC FOOTPRINTS

- SPECIAL REPORTS

- SUSTAINABILITY & CLIMATE CHANGE

- THIS WEEK'S TOP STORIES

- TRENDING

- UNCATEGORIZED

- UNITED NATIONS SDGS

Trending

-

TRENDING11 months ago

TRENDING11 months agoAFRIEF Congratulates New Zamfara State Governor

-

PROFILE8 months ago

PROFILE8 months agoA Salutary Tribute to General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida: Architect of Islamic Finance in Nigeria

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoClimate Policy In Indonesia: An Unending Progress For The Future Generation

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoThe Climate Crisis is Now ‘Code Red’: We Can’t Afford to Wait Any Longer

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoIPCC report: ‘Code red’ for human driven global heating

-

HALAL ECONOMY10 months ago

HALAL ECONOMY10 months agoRevolutionizing Halal Education Through Technology

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoThe Black sea protection initiative: What should we remember?

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY2 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY2 years agoDistributed Infrastructure: A Solution to Africa’s Urbanization