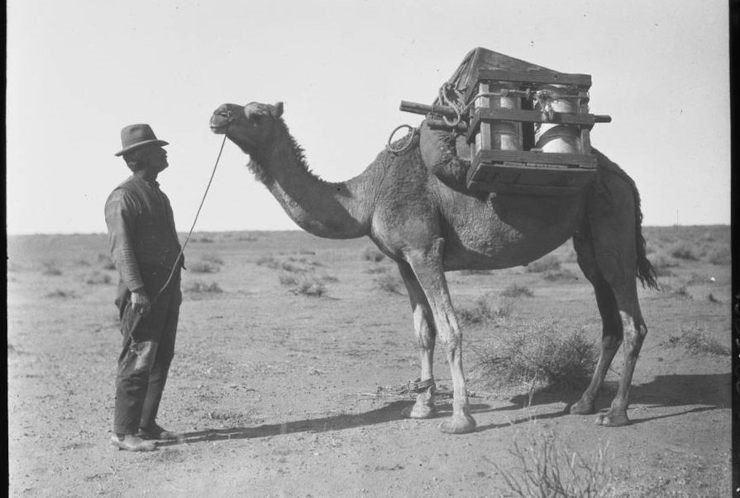

Afghan cameleers helped settle Australia’s interior.

There is a camel in Hanifa Deen’s kitchen. He looks down at her as she cooks, eyes proud yet warm, delicately flared snout-smelling dinner. While the creature is merely an image on a poster, Deen, who has written several books on Islam in Australia, regards him affectionately. “It looks like such a regal creature, such a haughty creature,” she says. That’s why you’ll only find camels decorating the walls of Deen’s kitchen, rather than filling a pot on her stove. “I admit, I can’t bring myself to eat a camel burger,” she says.

For many, disinterest in eating camel may sound natural. But around the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, and their diasporas, camel meat is dinner. In parts of Morocco, it’s stewed into fragrant tagines on special occasions. In Cairo, diners will pay a premium for the animal’s delicate fat. In Somali neighborhoods of the American Midwest, camel burgers offer immigrant communities, and curious neighbors, a fusion-inspired taste of home.

In contrast, most Australians, who are predominantly European in origin, come from cuisines unused to camel meat. Yet for a large lobby of Australian environmentalists, animal rights activists, and entrepreneurs—not to mention foodies—getting more camel into the Australian diet is not only a gustatory goal: It’s a solution to a major environmental problem.

That’s because Australia is home to the largest feral camel population in the world, with an estimated 300,000 to one million animals. The camels aren’t native to Australia: They were imported in the 19th century to explore the vast deserts of the country’s interior. Left to roam after the advent of motorcars, the population now poses a threat to both delicate ecosystems and local water supplies. In an attempt to address this environmental damage, the Australian government has sponsored aerial camel culls, in which feral camels are shot down by helicopter, their flesh left to rot in the sand. This outrages animal rights activists and many have suggested another way. Why not use feral camels for meat? In Australian neighborhoods home to recent Middle Eastern and African immigrants, after all, halal butcher shops already carry camel meat taken from the Outback, and the Australian camel-meat export industry is growing modestly.

The camel meat industry doesn’t just aspire to address the country’s feral camel conundrum. It also reveals the lingering legacy of a little-known aspect of Australian colonization. Recent Muslim immigrants to Australia present one potential market for the country’s fledgling camel-meat trade. Yet it was Australia’s first Muslim migrants who helped bring camels to Australia in the first place—and in doing so, enabled the settlement of the Australian interior.

In the 19th century, British colonists in Australia faced an endless desert. While Australia’s aboriginal people had thrived in the interior’s arid landscape for millennia, Europeans were stumped by the vast expanse. Was it flat or mountainous? Dry or a giant inland sea? Early expeditions failed to make much progress. European modes of exploration, including by horse, weren’t suited to the terrain.

Inspiration came from elsewhere in the Empire. The British had come into contact with camels in their colonial holdings in India, where camels and their drivers had traveled Northwest India’s Thar desert for centuries. In 1858, The Victorian Exploration Committee tasked horse dealer George Landell with recruiting camels and their drivers from India. When explorers Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills set off on their famous 1860 trek across the Australian continent, they brought camels with them. Hardy, steady, and dependable, able to trek for miles under the brutal sun with very little water, camels became an invaluable part of the overland network of goods, labor, and infrastructure that enabled the settlement of Australia’s interior. In the latter half of the 19th century, Australians would import an estimated 20,000 camels to the continent.

Camel handlers came with them. Called “Afghan cameleers,” an estimated 3,000 of these mostly Muslim men migrated to Australia. They weren’t all from Afghanistan—many came from British North India—but white Australians dubbed them all “Afghan,” and the name stuck, says Philip Jones, Senior Curator of Anthropology at the South Australian Museum. Despite the careless nomenclature, the cameleers’ significance was acknowledged by some white Australian officials. “It is no exaggeration to say that if it had not been for the Afghan and his Camels,” wrote one white Australian official in 1902, then “Wilcannia, White Cliffs, Tibooburra, Milperinka, and other Towns, each center of considerable population, would have practically ceased to exist.”

Yet the settling of Australia’s interior was, like the rest of the British colonial project, underlined by a toxic cocktail of racial pseudoscience. The Muslim cameleers, especially those who came from what is now Afghanistan, were regarded as “the aboriginal natives of Asia,” says Nahid Afrose Kabir, a historian, and sociologist who has written a book on the history of Australian Muslims. While the cameleers may have escaped the more extreme violence visited by Europeans on Australian Aboriginal communities, white Australians’ belief in the Muslims’ racial inferiority, coupled with competition over scarce Outback drinking water, boiled over into occasional racial violence.

“The Afghans and their camels are the filthiest lots that ever went near water,” wrote one Australian official in 1893. Tensions exploded in 1894, when a white Australian, Tom Knowles, shot and killed two cameleers, Noor Mahomet and Jehan Mohamet, as they performed wudu, the ritualistic washing before namaz or Muslim prayers, in a Western Australian spring. A jury found Knowles not guilty.

The cameleers set up enduring networks of infrastructure and trade, but they were mostly transitory. This was partly the nature of their profession: Even in India, cameleers were accustomed to undertaking long, rough, episodic voyages on contract. But it was also by Australian government design. By the late 19th century, calls for Australia to become a country of its own were mounting. Nationalism brought a wave of heightened racism. In 1901, the new Australian nation codified these racist sentiments into law. Collectively called the White Australia policy, these immigration laws barred immigrants pending their successful completion of Byzantine “language tests,” administered in any European language immigration officers pleased. Like the “literacy tests” of the U.S. Jim Crow South, these tests were about race, not language; the arcane requirements magically loosened for European applicants. The policy halted almost all non-white immigration until the Australian government relaxed enforcement in the 1970s.

Combined with the advent of motorized transport, the White Australia policy meant there was no place left for the Afghan cameleers. By the 1920s, the vast majority of them left the country. Their camels remained behind. Some of them were shot under the South Australian Camels Destruction Act of 1925. Others were released into the wilderness, where they continue to thrive to this day.

While the most visible, feral camels aren’t the only mark the cameleers left on Australia. Several of their mosques, like those in Perth and Adelaide, continue to host religious services. Meanwhile, descendants of the 300 or so cameleers who stayed and married white or Aboriginal women still live in parts of South Australia, recognizable by their surnames and their family pride.

Hanifa Deen’s affection for camels may stem from this legacy. Growing up in one of the few Muslim families in Perth, Deen attended a mosque alongside a few of the remaining cameleers. They seemed ancient. “I’d see all these old men, bearded with their turbans, pulling on their hookahs slowly and swaying as if caught up in a dream from another world,” she says.

When she began doing research on the cameleers for a book project, Deen was struck by the vitality of the young men in archival photographs. They were vibrant, hopeful, and very, very handsome. “My main problem was who was I going to marry,” she jokes. But in one photo, a strangely familiar face gave her pause: It was her grandfather. A businessman, he had migrated to Australia from British India in the late 19th century. His wife briefly joined him, and their son, Deen’s father, was born on the continent. While as a child he returned to South Asia with his mother, he eventually settled in Australia.* Growing up in majority-white Australia, Deen rarely heard official histories of people like her family. The reason for this omission, she says, is obvious: “Who writes the history books?”

Now, Deen and other Australian Muslims are remedying this historical erasure by writing history books themselves. Thanks to these efforts and education initiatives from institutions such as the Islamic Museum of Australia, the past couple of decades have brought increasing recognition of the cameleers’ role in Australian history to the mainstream. Kabir says this is especially important in the wake of recent, brutal Islamophobic attacks like the Christchurch mosque shooting, which was committed by a white Australian.

Meanwhile, the very groups Australia once excluded may just hold the key to solving—at least in part—the country’s feral camel dilemma. From halal butcher shops to wholesalers exporting camels to the Middle East, Australia’s camel meat trade is on the up. The industry faces challenges, primarily among them the difficulty of transporting feral camels and fresh meat across the Outback. But lovers of camel meat say it’s worth it for the taste alone: like a cross between lamb and beef, mostly lean but with pockets of sweet, delicate fat. Camel meat is so good, one Somali-Australian butcher told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, it’s only a matter of time before European Australians catch on. When they do, they can thank the Afghan cameleers.