BUSINESS & ECONOMY

We Can’t Breathe: How Africans Suffocate Themselves With Debt

Published

1 year agoon

By

Editor

By Abimbola Agboluaje

Economic activities have taken a massive clobbering from the measures in place all over the world to curtail the spread of the new coronavirus. According to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook Update, June 2020, global economic output will shrink by 4.9% in 2020, 1.9% lower than the IMF’s April 2020 forecast. For African economies as all others in the world, this means not only job losses but lost incomes from exports and reduced tax revenues. But while governments in other regions have rolled out billions of dollars in fiscal interventions to stimulate economic activities and /or support the jobless, African Governments have to look for $44 billion to service debts in 2020. Even before the economic ravage of the new coronavirus, many African countries spent more money servicing debt in 2019 than they spent on healthcare.

The IMF June 2020 Update forecasts a 3.2% decline in economic growth for Sub-Saharan Africa with output in the regional economic powerhouses, Nigeria and South Africa declining by 5.4% and 8.0% respectively. Without debt relief, Nigeria will use 96% of its income to service debt in 2020. Contrasting the plight of African countries with their western counterparts, Ken Ofori-Atta, the Minister of Finance of Ghana, exclaimed at a Centre of African Studies, University of Harvard webinar on June 3, 2020 “You really feel like shouting ‘I can’t breathe’ “. The G20 nations have agreed to let African debtors defer $20 billion debt payment until the end of 2020. But this applies mostly to debts owed to Western and other G20 governments.

Why Debt Relief Now Offers Very Little Comfort

The debts which burdened African economies in the 1980s and 1990s were predominantly contracted through Export Credit Agencies of Western Governments which guaranteed payments by African countries for goods and services their (private) companies exported to Africa. (The debts were not owed to the World Bank or IMF as is widely believed). In 1990, 83% of Africa’s debt stock i.e. $255 billion was owed to official creditors while only $28 billion was owed to private creditors. In the last ten years African Governments have expanded their search for credit and financing beyond western export credit and aid agencies and multilateral development agencies like the World Bank, IMF, and the African Development Bank which are significantly funded and controlled by western nations. They started to borrow from western investors by issuing bonds in London and New York just like western governments. According to 2020 data compiled by the World Bank, Africa owes $493.6 billion in long-term debt 33% of which consists of commercial debts, specifically bonds.

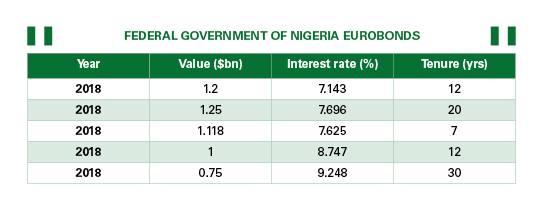

According to The Economist, 8 African countries issued 30-year bonds in 2018. This growing trend of commercial borrowing is problematic for two reasons. First, investors in the bonds are completely profit-oriented and are much less persuaded by arguments that not granting debt relief would hamstring economies and increase poverty. Also, unlike development agencies’ lending which is usually priced between 1% and 3% and is payment-free for the initial 3 or 5 years, commercial lending is very expensive and thus contributes to raising Africa’s debt burden. The interest on the 30-year Nigerian Euro bond is 9.248%, compared to the 0.031% interest rate on 30-year German bonds. Nigerian Government officials used to celebrate the fact that Nigerian Eurobonds were oversubscribed i.e. there were more investors than bonds to sell. This is almost like leaving wads of dollars on the street and being surprised to see many people pocketing them. The higher price Nigeria pays to borrow is a reflection of the perceived risk of default; Germany has AAA credit rating with all the major 3 credit rating agencies.

Bonds are purchased by hundreds of investors; any decision on debt relief or restructuring or deferring interest payment has to be collectively agreed upon. It is notoriously difficult to agree on terms of debt restructuring amongst investors. Nigeria spent $771 million on interest on its Eurobonds in 2019, more than double the $329 million it paid to multilateral creditors. Like other African newcomers to commercial debt, Nigeria is wary of asking bondholders for debt restructuring. While it isn’t certain that the request would be granted, the mere act of asking would automatically result in a credit rating downgrade and complicate issuing Eurobonds in the future.

Commercial Debt: An Act of Financial Self-Suffocation

When poor countries’ governments experience fiscal crises, often as a result of the collapse of commodity prices, and debtors demand they hand over the limited funds they have to fund schools and hospitals, they resort to emotional blackmail such as complaining that they can’t breathe or that they are being encircled by financial vultures. Their citizens and supporters in the West seldom examine their own complicity in creating the lock hold.

The former IMF Managing Director, Christine Lagarde visited Nigeria in January 2016 to discuss how the institution could assist Nigeria to cope with the loss of $11 billion due to the fall in oil prices. She made it clear that the IMF could lend to Nigeria at 1%. Nigeria rejected the offer for 7 to 8% commercial debt (through issuing Eurobonds). IMF loans come with conditions. Nigeria would have had to undertake policy reforms that enable it to use its own resources more productively, diversify its economy, and thus make its economy less susceptible to external shocks. IMF conditions would have included requesting that Nigeria spent more on healthcare and education or on roads rather than on fuel subsidy. The IMF would also have asked that Nigeria collapsed its multiple exchange rates, in effect a devaluation, which would have prevented the Central Bank of Nigeria from using more than $40 billion of its reserves to defend the naira over 3 years.

According to Franklin Cudjoe, President of the Accra-based Imani, one of Africa’s foremost economic policy think tanks, Ghana has issued Eurobonds mostly for infrastructure projects “that do not necessarily return value in the short to medium term”. In an interview with Arbiterz, Cudjoe expressed the opinion that investment in freight-carrying railway would have aided Ghana to reduce non-tariff barriers to regional trade; the passenger trains that Ghana has invested in cannot compete with road transport. Cudjoe also believes that Eurobond proceeds should not be invested in healthcare as the public sector is “just inefficient at maintenance and offering proper care”. He advises that Ghana and the rest of Africa use a mix of private sector investment and management of hospitals and private health insurance firms to “provide tiered but humane healthcare coverage.” Similarly Misheck Mutize of the Graduate School of Business (GSB), University of Cape Town noted that African countries use Eurobonds to finance loss-making projects like the Kenyan Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) which do not generate new economic activity and/or are not self-sustaining.

Investors in Eurobonds are interested in getting handsome returns rather than poverty alleviation or sustainable monetary policies, so their lending comes with no conditions on improving economic policies. Funds from commercial lending are “fungible” i.e. African countries are often able to divert the funds to uses other than those stated for issuing Eurobonds. Commercial loans clearly have allowed many African countries to avoid critical reforms that would have boosted economic growth and contributed to reducing poverty, diversifying, and insulating their economies from external shocks. Now they have to hand over billions of dollars to service the loans.

The Director-General of Nigeria’s Debt Management Office, Patience Oniha, said at an investor conference on 23 June 2020 that Nigeria will until further notice borrow locally and seek international concessional lending rather than issue Eurobonds. This self-denial is very conveniently timed. There is simply no investor appetite for Nigerian Eurobonds in financial markets scarred by the new coronavirus pandemic; Nigeria had to scrap plans to issue yet another $3.3 billion Eurobond in March 2020. It is safe to conclude that Nigeria, for now, prefers the exorbitant privilege of commercial borrowing over reforms that would unleash genuine and sustainable economic growth. The country is likely to start issuing Eurobonds again once global economic conditions improve and financial markets regain their risk appetite.

Should Africa avoid the Vultures?

The poor quality of economic policy and institutions are the primary explanations for Africa’s underdevelopment and poverty rather than the lack of capital for public investment. But efficient mobilisation and investment of capital will significantly improve economic outcomes as well as the quality of economic policy.

Africa’s severe shortage of infrastructure is a barrier to investment and productivity and improving livelihoods. According to the World Bank, Africa needs to invest $90 billion every year in infrastructure but faces a $31-$40 billion shortfall. African countries should hence endeavour to access all available sources of capital to boost public investment, especially the very liquid western bond markets where western governments raise capital for their vastly greater public investment. In 2018, the value of outstanding bonds in the global bond market was $102.8 trillion, compared to $74.7 billion capitalization of the global equity market. In 2018, members of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation in Europe, a club for the world’s richest economies, issued bonds worth $10.7 trillion, far more money than Africa has ever received in development aid since independence. African countries are determined to preserve access to this market precisely because they are aware it could easily finance their comparatively modest investment needs. The question is how to ensure that access to western bond markets assists in closing Africa’s infrastructure gaps rather than primarily to deliver supernormal profits to investors.

Africa will not transform the legacy of poor governance overnight. But it is quite possible to improve significantly policy and governance around an oasis of infrastructure projects which African Governments aim to finance with Eurobonds. The prospectuses of African countries are often vague about the intended specific uses of proceeds of Eurobonds. Simple things like initiating policies that ensure that proceeds from Eurobonds could only be invested in the infrastructure projects for which the bond was issued would not only enable African countries negotiate lower interest rates but would also enhance economic growth and thus the capacity to repay debt. African governments should aim to finance infrastructure for which there is a clear economic need and for which economic user fees could be charged with their new Eurobonds whenever it becomes possible again to approach the market.

Selective Regional Integration and External Agencies of Restraint

All politicians would prefer short-term fiscal choices that enable them deliver free or subsidised healthcare, education and infrastructure services and avoid hard choices about sustainability while storing up economic crises and failure. In developed economies, think-tanks, the media, opposition political parties, legislatures, etc. act as, according to the Oxford economist Paul Collier, “agencies of restraint” on governments’ fiscal choices. In most African countries, “epistemic communities” i.e. academics, policy experts, and journalists that research, generate and diffuse knowledge about the consequences of fiscal or economic policy choices are very poorly resourced and have little influence. And political institutions, including legislatures, tend to serve as “agencies of distribution” in African politics rather than of restraint because the political argument over fiscal policies in ethnically divided African politics is more about the identity of beneficiaries and less about economic impact or sustainability.

The Cameroonian economist and Head of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Vera Songwe, has suggested the creation of a new institution that could issue bonds for African countries at much lower interest rates by guarantying repayment. This is a very good idea worth exploring. But only western governments or the development finance institutions they control could offer investors the required level of comfort required to sufficiently de-risk African debt. African integration initiatives tend to converge around the lowest common denominator rather than set high standards for “upwards” policy convergence. Unlike the European Union, for instance, economic integration processes in Africa do not act as an external restraint on domestic policy choices.

African governments who have been happy to use access to very expensively priced bonds in order to avoid fiscal and economic reforms are very unlikely to act together to create a credible structure that would enable them borrow at lower interest rates. (Leaving aside having the funds or creditworthiness to guarantee repayment of debt if countries issuing bonds default). External actors like the European Union which through the European Development Fund has had a multilateral instrument for conducting development policy negotiations with African countries (alongside Caribbean and Pacific nations) for decades is well-positioned to create an institution for helping Africa tap bond markets at much lower interest rates (ideally not higher than 2.5%). The new structure has to work on the principle of “selective integration” i.e. open to only countries who want to use Eurobonds to finance economically viable projects even if European funders have to invest in selling it to African governments and citizens. Europe would be doing for Africa what America did for it after the Second World War through the Marshall Plan when the Yankees’ European Cooperation Administration (ECA) produced a large publicity campaign comprising pamphlets, posters, radio broadcasts, traveling puppet shows, and over 250 films between 1949-1953 to convince Europeans of the wisdom to adopt American methods of managerial and economic organisation. The technical arguments about how to lower the interest African pay to issue debt on western bond markets are unassailable, the problem is selling them to African citizens and their governments.

Courtesy: Arbiterz

You may like

BUSINESS & ECONOMY

In Times of Conflict, Spare a Thought for the Non-Gulf Economies

Published

1 week agoon

May 6, 2024By

Editor

By James Swanston

Positive news for non-GCC Arab economies has been in short supply of late. The Gaza conflict, missile attacks in the Red Sea, war in Ukraine and last month’s tit-for-tat missile strikes between Israel and Iran have weighed on sentiment, undermined limited confidence and cut into growth.

But some positives have emerged. Headline inflation rates have slowed across much of North Africa and the Levant, implying lower interest rates, a return to real growth and more stable exchange rates. March data show inflation at an annualised rate of just 0.9 percent in Morocco and 1.6 percent in Jordan. Tunisia’s inflation rate has also come down, although it is still running at over 7 percent year on year.

Egypt’s inflation rate jumped earlier this year as the government implemented price hikes to some goods and services – notably fuel. In February, the effect of the devaluation in the pound to the level of the parallel market affected prices. But March’s reading eased to an albeit still high 33 percent year on year.

Elsewhere, Lebanon’s inflation slowed to 70 percent year on year in March, the first time it has been in double – rather than triple – digits since early 2020 due to de-facto dollarisation and lower demand for imports. That said, inflation in these economies is vulnerable to increases in the prices of global foods and energy (such as oil) due to their being net importers. If supply chain disruptions persist, it could result in central banks keeping monetary policy tighter with consequences for growth and employment. And in Morocco’s case, it could undermine the Bank Al-Maghrib’s intention to widen the dirham’s trading band and formally adopt an inflation-targeting monetary framework.

The strikes by Iran and Israel undoubtedly marked a dangerous escalation in what up to now had been a proxy war. Thankfully, policymakers across the globe have for the moment worked to de-escalate the situation. Outside the countries directly involved, the most significant spillover has been the disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Many of the major global shipping companies have diverted ships away from the Red Sea due to attacks by Houthi rebels and have instead opted to go around the Cape of Good Hope.

The latest data shows that total freight traffic through the Suez Canal and Bab el-Mandeb Strait is down 60-75 percent since the onset of the hostilities in Gaza in early October. Almost all countries have seen fewer port calls. This could create fresh shortages of some goods imports, hamper production, and put upward pressure on prices.

For Egypt, inflation aside, the shipping disruptions have proven to be a major economic headache. Receipts from the Suez Canal were worth around 2.5 percent of GDP in 2023 – and that was before canal fees were hiked by 15 percent this January. Canal receipts are a major source of hard currency for Egypt and officials have said that revenues are down 40-50 percent compared to levels in early October.

The conflict is also weighing on the crucial tourism sector. Tourism accounts for 5-10 percent of GDP in the economies of North Africa and the Levant and is a critical source of hard currency inflows.

Jordan, where figures are the timeliest, show that tourist arrivals were down over 10 percent year on year between November and January. News of Iranian drones and missiles flying over Jordan imply that these numbers will, unfortunately, have fallen further.

In the case of Egypt, foreign currency revenues – from tourism and the Suez canal – represent more than 6 percent of GDP and are vulnerable. This played a large part in the decision to de-value the pound and hike interest rates aggressively in March.

The saving grace is that the conflict has galvanised geopolitical support for these economies. For Egypt, the aforementioned policy shift was accompanied by an enhanced $8bn IMF deal and, while not strictly bilateral support, the bumper Ras el-Hekma deal seems to have been accelerated as the pressure on the Egyptian economy ratcheted up. This is providing much needed foreign currency. At the same time, Jordan recently renewed its financing arrangement with the IMF for $1.2bn over four years.

Tunisia, however, is an exception. President Saied’s anti-IMF rhetoric and reluctance to pass reforms, such as harsh fiscal consolidation, in an election year, mean that the country’s staff-level agreement for an IMF deal is likely to remain in limbo. If strains on Tunisia’s foreign receipts are stretched, and the central bank and government continue with unorthodox policies of deficit financing, there is a risk that Tunisia’s economic crisis will become messier more quickly in the next year – particularly large sovereign debt repayments are due in early 2025.

James Swanston is Middle East and North Africa economist at London-based Capital Economics

BUSINESS & ECONOMY

Debt Dependency in Africa: the Drivers

Published

1 week agoon

May 6, 2024By

Editor

In mid-April Ghana’s efforts to restructure its sovereign debt came to nothing, increasing the risk that it couldn’t keep up with its repayments. This is a familiar story for many African countries. Twenty of them are in serious debt trouble. Carlos Lopes argues that there are three factors driving this state of affairs: the rules of the international banking system; lenders’ focus on poverty reduction rather than development needs; and unfair treatment by rating agencies.

The debt situation in many African countries has escalated again to a critical juncture. Twenty are in, or at risk of, debt distress. Three pivotal elements significantly contribute to this. Firstly, the rules governing the international banking system favour developed countries and work against the interests of African countries.

Secondly, multilateral financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank focus on poverty alleviation. This is commendable. But it doesn’t address the liquidity crisis countries face. Many don’t have the necessary readily available funds in their coffers to cover urgent development priorities due to their dependency on volatile commodity exports. As a result governments turn to raising sovereign debt under conditions that are among the most unfavourable on the planet. This perpetuates a debt dependency cycle rather than fostering sustainable economic growth.

Thirdly, there’s the significant influence of biased credit rating agencies. These unfairly penalise African countries. In turn, this impedes their ability to attract investment on favourable terms. The convergence of these three factors underscores the imperative to implement effective strategies aimed at mitigating the overwhelming debt burden afflicting African nations. These strategies must address the immediate financial challenges facing countries. They must also lay the groundwork for long-term economic sustainability and equitable development across the continent.

By tackling these issues head-on, a financial environment can be created that fosters growth, empowers local economies, and ensures that African countries have access to the resources they need to thrive.

Rules of the banking game

The Bank for International Settlements is often called the “central bank for central banks”. It sets the regulations and standards for the global banking system. But its rules disproportionately favour developed economies, leading to unfavourable conditions for African countries. For instance, capital adequacy requirements – the amount of money banks must hold in relation to their assets – and other prudential rules may be disproportionately stringent for African markets. This limits lending to stimulate economic growth in less attractive economies.

The bank’s policies also often overlook developing nations’ unique challenges. Following the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the bank introduced a new, tougher set of regulations. Their complexity and stringent requirements have inadvertently accelerated the withdrawal of international banks from Africa.

They have also made it increasingly difficult for global banks to operate profitably in African markets. As a result, many have chosen to scale back their operations, or exit. The withdrawals have reduced competition within the banking sector, limited access to credit for businesses and individuals, and hampered efforts to promote economic growth and development.

The limitations of the new regulations highlight the need for a more nuanced approach to banking regulation. The adverse effects could be mitigated by simplifying the regulations. For example, requirements could be tailored to the specific needs of African economies, and supporting local banks.

Focus on poverty alleviation

Multilateral financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank play a crucial role in providing financial assistance to many countries on the continent. But their emphasis on poverty alleviation and, more recently, climate finance often overlooks the urgent spending needs. Additionally, the liquidity squeeze facing countries further limits their capacity to prioritise essential expenditure. Wealthy nations enjoy the luxury of lenient regulatory frameworks and ample fiscal space. For their part African countries are left to fend for themselves in an environment rife with predatory lending practices and exploitative economic policies. Among these are sweetheart tax deals which often involving tax exemptions. In addition, illicit financial practices by multinational corporations drain countries of their limited resources. Research by The ONE Campaign found that financial transfers to developing nations plummeted from a peak of US$225 billion in 2014 to just US$51 billion in 2022, the latest year for which data is available. These flows are projected to diminish further.

Alarmingly, the ONE Campaign report stated that more than one in five emerging markets and developing countries allocated more resources to debt servicing in 2022 than they received in external financing. Aid donors have been touting record global aid figures. But nearly one in five aid dollars was directed towards domestic spending hosting migrants or supporting Ukraine. Aid to Africa has stagnated.

This leaves African countries looking for any opportunities to access liquidity, which makes them a prey of debt scavengers. As noted by Columbia University professor José Antonio Ocampo, the Paris Club, the oldest debt-restructuring mechanism still in operation, exclusively addresses sovereign debt owed to its 22 members, primarily OECD countries.

With these limited attempts to address a significant structural problem of pervasive indebtedness it is unfair to stigmatise Africa as if it contracted debt because of its performance or bad management.

Rating agencies

Rating agencies wield significant influence in the global financial landscape. They shape investor sentiment and determine countries’ borrowing costs. However, their assessments are often marked by bias. This is particularly evident in their treatment of African countries. African nations argue that without bias, they should receive higher ratings and lower borrowing costs. In turn this would mean brighter economic prospects as there is a positive correlation between financial development and credit ratings. However, the subjective nature of the assessment system inflates the perception of investment risk in Africa beyond the actual risk of default. This increases the cost of credit.

Some countries have contested ratings. For instance, Zambia rejected Moody’s downgrade in 2015, Namibia appealed a junk status downgrade in 2017 and Tanzania appealed against inaccurate ratings in 2018. Ghana contested ratings by Fitch and Moody’s in 2022, arguing they did not reflect the country’s risk factors. Nigeria and Kenya rejected Moody’s rating downgrades. Both cited a lack of understanding of the domestic environment by rating agencies. They asserted that their fiscal situations and debt were less dire than estimated by Moody’s.

Recent arguments from the Economic Commission for Africa and the African Peer Review Mechanism highlight deteriorating sovereign credit ratings in Africa despite some posting growth patterns above 5% for sustained periods. Their joint report identifies challenges during the rating agencies’ reviews. This includes errors in publishing ratings and commentaries and the location of analysts outside Africa to circumvent regulatory compliance, fees and tax obligations.

A recent UNDP report illuminates a staggering reality: African nations would gain a significant boost in sovereign credit financing if credit ratings were grounded more in economic fundamentals and less in subjective assessments. According to the report’s findings, African countries could access an additional US$31 billion in new financing while saving nearly US$14.2 billion in total interest costs.

These figures might seem modest in the eyes of large investment firms. But they hold immense significance for African economies. If credit ratings accurately reflected economic realities, the 13 countries studied could unlock an extra US$45 billion in funds. This is equivalent to the entire net official development assistance received by sub-Saharan Africa in 2021. These figures underscore the urgent need to address the systemic biases plaguing credit rating assessments in Africa.

Next steps

Debates about Africa’s debt crisis often lean towards solutions centered on compensation. These advocate for increased official development aid, more generous climate finance measures, or the reduction of borrowing costs through hybrid arrangements backed by international financial systems. These measures may offer temporary relief. But they need to be more genuine solutions in light of the three structural challenges facing African countries.

Carlos Lopes,a Professor at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town, is the Chair of the African Climate Foundation’s Advisory Council as well as its Chairman of the Board. He is also a board member of the World Resources Institute and Climate Works Foundation.

Courtesy: The Conversation

BUSINESS & ECONOMY

IsDB President Advocates for Cultivating Entrepreneurial Leaders

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 30, 2024By

Editor

By Hafiz M. Ahmed

The 18th Global Islamic Finance Forum recently served as a prominent platform for discussions on advancing Islamic finance and fostering leadership in the entrepreneurial sector. During this notable event, the President of the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) emphasized the critical need for nurturing entrepreneurial leaders to propel the growth of the Islamic finance industry. This blog post explores the insights shared by the IsDB President, the implications for the future of Islamic finance, and the strategies proposed to develop the next generation of leaders.

Key Highlights from the Forum

The Global Islamic Finance Forum, held annually, brings together experts, policymakers, and stakeholders from across the world to deliberate on the challenges and opportunities within Islamic finance. This year’s focus on entrepreneurial leadership underscores the sector’s evolution and its growing impact on global economies.

The IsDB President’s Vision

- Empowering Entrepreneurs. The IsDB President outlined a vision where empowerment and support for entrepreneurs are paramount. He highlighted the role of Islamic finance in providing ethical and sustainable funding options that align with the principles of Sharia law, offering a robust alternative to conventional financing methods.

- Education and Training. A significant part of the address was dedicated to the importance of education and specialized training in Islamic finance. The President called for enhanced educational programs that not only focus on the technical aspects of Islamic finance but also foster entrepreneurial thinking and leadership skills among students.

- Innovation in Financial Products. Recognizing the rapidly changing financial landscape, the call for innovation in designing financial products that meet the unique needs of modern businesses was emphasized. These innovations should aim to enhance accessibility, affordability, and suitability for diverse entrepreneurial ventures.

- Collaborative Efforts. The IsDB President advocated for increased collaboration between Islamic financial institutions and educational entities to create ecosystems that support and nurture future leaders. This collaboration is essential for developing a holistic environment where aspiring entrepreneurs can thrive.

- Supportive Policies: Lastly, the need for supportive governmental policies that facilitate the growth of Islamic finance was discussed. Such policies should encourage entrepreneurship, particularly in regions where access to financial services is limited.

Implications for the Future

The advocacy for entrepreneurial leaders in Islamic finance is timely, as the industry sees exponential growth and wider acceptance as a viable financial system globally. Cultivating leaders who not only understand the intricacies of Islamic finance but who are also capable of innovative thinking and ethical leadership is crucial for the sustainability and expansion of this sector.

Steps Forward

- Integrating Leadership into Curriculum: Educational institutions offering courses in Islamic finance should integrate leadership training into their curricula.

- Mentorship Programs: Establishing mentorship programs that connect experienced professionals in Islamic finance with emerging leaders.

- Fostering Start-up Ecosystems: Creating supportive environments for start-ups within the Islamic financial framework can encourage practical learning and innovation.

Conclusion

The call by the IsDB President to nurture entrepreneurial leaders in Islamic finance is a step toward ensuring the sector’s robust growth and its contribution to global economic stability. By focusing on education, innovation, and supportive policies, the Islamic finance industry can look forward to a generation of leaders who are well-equipped to navigate the complexities of the modern financial world and who are committed to ethical and sustainable business practices. This vision not only enhances the profile of Islamic finance but also contributes to a more inclusive and balanced global financial ecosystem.

Turkey’s Bold Stand Against Israeli Aggression in Gaza: A Call for Global Solidarity

What is Microtakaful and How Does It Work?

Top 8 Ways Halal Cosmetics Are Reshaping Fashion in 2024

Topics

- AGRIBUSINESS & AGRICULTURE

- BUSINESS & ECONOMY

- DIGITAL ECONOMY & TECHNOLOGY

- EDITORIAL

- ENERGY

- EVENTS & ANNOUNCEMENTS

- HALAL ECONOMY

- HEALTH & EDUCATION

- IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

- INTERNATIONAL POLITICS

- ISLAMIC FINANCE & CAPITAL MARKETS

- KNOWLEDGE CENTRE, CULTURE & INTERVIEWS

- OBITUARY

- OPINION

- PROFILE

- PUBLICATIONS

- SPECIAL FEATURES/ECONOMIC FOOTPRINTS

- SPECIAL REPORTS

- SUSTAINABILITY & CLIMATE CHANGE

- THIS WEEK'S TOP STORIES

- TRENDING

- UNCATEGORIZED

- UNITED NATIONS SDGS

Trending

-

TRENDING11 months ago

TRENDING11 months agoAFRIEF Congratulates New Zamfara State Governor

-

PROFILE9 months ago

PROFILE9 months agoA Salutary Tribute to General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida: Architect of Islamic Finance in Nigeria

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoClimate Policy In Indonesia: An Unending Progress For The Future Generation

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoThe Climate Crisis is Now ‘Code Red’: We Can’t Afford to Wait Any Longer

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoIPCC report: ‘Code red’ for human driven global heating

-

HALAL ECONOMY10 months ago

HALAL ECONOMY10 months agoRevolutionizing Halal Education Through Technology

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY2 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY2 years agoDistributed Infrastructure: A Solution to Africa’s Urbanization

-

SPECIAL REPORTS5 months ago

SPECIAL REPORTS5 months agoRemembering Maryam Ibrahim Babangida: A Legacy of Grace, Philanthropy, and Leadership