BUSINESS & ECONOMY

The Upcoming Recession and its Ramifications on World Economies

Published

1 year agoon

By

Editor

By Rahul Ajnoti

The recent decision of the new head of Twitter, Elon Musk, to sack approximately 50 percent of the workforce is only indicative of the recession that is glooming over the world. The story of Twitter is just one example among many visible ones. Almost all the major firms around the globe have or are planning to lay off employees, including Microsoft, Meta, Tencent, Xiaomi, Unacademy, etc.

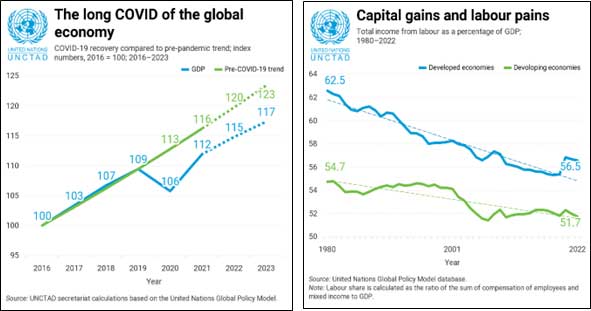

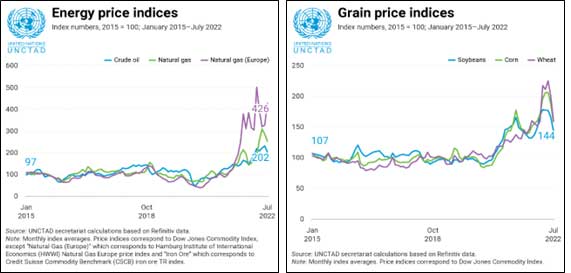

According to a comprehensive study titled ‘Risk of Global Recession in 2023 Rises Amid Simultaneous Rate Hikes’ by the World Bank, all the nation-states are tilting towards a cascade of economic crises in global financial markets and emerging economies, leading to long-term damages. The report blames central banks around the globe for raising interest rates to tackle inflation caused due to the Coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s aggression on Ukraine in the European arena. The report states that even raising the interest rates to an unprecedented high not seen over the past five decades will be insufficient to pull global inflation down to the pre-pandemic levels. It further instils the need to focus on supply disruptions and subside labour-market pressures. The President of the World Bank Group, David Malpass urged policymakers to focus on boosting production instead of cutting consumption and make policies that generate auxiliary investments, improving productivity and capital allocation, which are crucial for growth.

Economics 101: Recession

Amidst the pandemic, many states released relief and stimulus packages that heavily leaned on measures to expand liquidity, such as loosening lending restrictions or reducing repo rates (the rate at which commercial banks borrow money from the central bank) as well as reverse repo rates (the rate at which commercial banks lend money to the central bank). China was the first state to act upon these stimulus measures to counteract the disruptions caused by the covid, followed by Japan, the EU, Germany, India and so on. Though the measures helped economies absorb the pandemic’s impact, one major drawback was increased demand due to induced money flow in the market, leading to inflation.

Inflation, defined as the rate of increase in prices of general goods and commodities in a given period of time, can be caused by multiple factors. A shortfall in aggregate supply, one of the most common factors, can lead to excessive demand pressures in the market. To curb inflation, central banks often tweak or change the fiscal and monetary policies of the nation. Increasing the interest rates is one such measure, as it tightens the economy’s banking system and thus contracts the flow of money, reducing already high demands. However, suppose only the rates are increased without substantial reforms in line with resetting the supply chains, increasing production and overall growth to meet the demand; in that case, a country may move towards a recessionary period. Therefore, alongside rising rates, a nation must diversify its suppliers, invest in technology (without increasing the debt burden), and focus on self-reliance while sustaining employment.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) defines recession practically as the fall in a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), i.e. a decline in the value of all the produced goods and services in a country for two consecutive quarters. Simply, a recession is a period of massive economic slowdown. Pointing at a specific moment when a recession occurs is almost impossible and futile. However, a few indicators, like the downfall of GDP and public spending, increased unemployment, and a decline in sales and a country’s output, generally point towards an upcoming recession. To sum up, there are various ways for a recession to start, from sudden shocks to the economy and excessive debt to uncontrolled inflation (or deflation) and non-performing asset bubbles.

The Stumbling Economies

According to IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, “First, Covid, then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and climate disasters on all continents have inflicted immeasurable harm on people’s lives.” One-third of the world economies, including the United States, Europe and China, are expected to contract in the subsequent quarters.

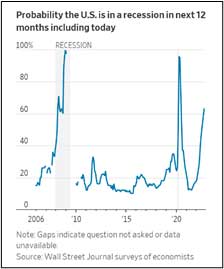

For US economists and forecasters, the recession is no longer about ‘if’ but ‘when’. The decision of the Fed (US Central Bank) to increase rates to cool inflation without inducing higher unemployment and an economic downturn has only shrunk the possibility of a ‘soft landing,’ which occurs when the tightened monetary policies of the Fed reduce inflation without causing a recession. Nouriel Roubini, one of the few economists who rightly predicted the financial crisis of 2008, also claims a prolonged and inevitable recession in 2022 that will last till 2023. Economists expect a growth rate of 0.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2023 as opposed to the fourth quarter of the previous year, and in 2024, they expect the economy to grow at 1.8 percent. The rate of unemployment is expected to rise to 3.7 percent in December this year and to 4.3 percent in June 2023, compared to 3.5 percent in September.

Like the US, Europe was also under the impression that the economic situation would improve without a recession. Assumptions of subsiding or transitory inflation due to solid businesses, enough public savings and adequate fiscal adjustments turned out wrong for the European economies. The Euro area (5.1 percent), and the UK (6.8 percent), are among the countries with the most expected output loss. Europe has mainly been affected by the Russian war on Ukraine and the resulting oil and gas disruptions leading to an ‘Energy War’ against the former. Similarly, China doesn’t lie far from them, with an expected output loss of 5.7 percent in 2023. Zero Covid Policy, coupled with the mortgage crisis and exodus in the manufacturing sector, has led to the economic slowdown of the Asian giant.

Impact on the Indian Economy

India reported a growth of 13.5 percent in the April to June quarter and became the world’s fifth-biggest economy, taking the spot of Great Britain. However, this growth results from the nation’s shutdown amid Delta-driven covid lockdowns during previous quarters and not because of the significant improvements in the economic activities. India needs to focus on skill-based human development projects to unleash its economic potential and effectively utilise its demographic dividend. However, India is not immune to the global slowdown. It is expected to face an output loss of 7.8 percent in 2023.

Indian CEOs are also expecting a decline in the growth of companies, but the economy is expected to bounce back in the short term, according to KPMG 2022 report. Moreover, 86 percent of CEOs in India expect an impact of up to 10 percent on earnings in the next 12 months. Reducing profit margins, boosting productivity, diversifying supply chains, and implementing a hiring freeze (worst case, layoff policies) are a few steps firms can take to weather such challenges.

India, thus, needs to tap the potential of start-ups and small enterprises, as opposed to just established firms, by expanding and enhancing the private sector’s access to capital investments and curbing environment-related risks. Reforms in dispute resolution mechanisms are also long overdue, evident through the Ease of Doing Business report, where India ranked 63rd out of 190 countries worldwide. India needs to prove its worth by showing investors that not only can their money achieve decent returns, but it is safe in Indian soil as well.

The stand on India’s future remains split. The global rating agency S&P claims that India will not face the true and horrifying brunt of the global recession thanks to its decoupled economy with huge domestic demand, healthy balance sheets and enough foreign exchange reserves. On the contrary, according to the Japanese brokerage firm- Nomura, policymakers are misplaced in their optimism about India’s growth trajectory. Its economists assert India’s estimated growth at 7 percent in FY23, which is at par with the RBI’s revised forecasts, but it also predicts a sharp decline to 5.2 percent in FY24. This estimated growth doesn’t align with India’s commitment to becoming a 5 Trillion USD economy.

Way Forward

UNCLAD’s Trade and Development Report 2022 projects global economic growth will plunge down to 2.5 percent in 2022, followed by a drop to 2.2 percent in 2023, costing the world a loss of more than 17 trillion USD in productivity. It further warns that the developing nations will be most vulnerable to the slowdown resulting in a cascade of health, debt and climate crises. Regarding the proportion of revenue to public debt, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Angola, Gabon, and Laos are the worst-hit countries, evident through the excessive inflation these states face.

Similarly, Indian fuel and food commodities prices have increased, but India’s sturdy performance when other countries are struggling can be attributed to its efficient policies. India does not have a perpetual external debt burden to hamper its growth. In addition, the government has focussed on developing the industrial and service sector to promote jobs and increase savings, especially after the Pandemic, to revitalise the Indian economy. Domestically, the government has provided effective social safety nets to ensure healthy livelihood for the population.

Despite these factors, India must realize and accept the harsh reality of the upcoming turbulent times. India may have a decoupled economy, but the world is one interlinked system. Global slowdowns will lead to a recession in India as well, whose effects are becoming more and more visible with each passing day. Major tech firms in India like Wipro, Tech Mahindra and Infosys have revoked their offer letters to young freshers, while others have started laying off employees amidst the fear of global recession. Irrespective of whether India becomes the “fastest growing economy” in the end, even a modest growth rate of about 5 percent will push millions into poverty in a country like India. It’s only imperative to realise that a depreciating currency and elevated inflation will hit the poorest the hardest, and India must be prepared to deal with this challenge.

Courtesy: Modern Diplomacy

You may like

BUSINESS & ECONOMY

ICD and JSC Ziraat Bank Collaborate to Boost Uzbekistan’s Private Sector

Published

2 days agoon

May 16, 2024By

Editor

At the 3rd Tashkent Investment Forum, the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD) and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan took a significant step forward in their partnership to empower small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and foster economic growth in Uzbekistan. The forum, held in the capital city of Uzbekistan, brought together key stakeholders from the public and private sectors to discuss investment opportunities and economic development strategies for the region. The collaboration between the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD) and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan is aimed at boosting the private sector in Uzbekistan.

During the forum, ICD and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan formalized an expression of intent to collaborate on various initiatives aimed at supporting SMEs. One of the key elements of this collaboration is the provision of a Line of Financing (LoF) facility by ICD to JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan. This LoF facility will enable the bank to fund private sector projects as an agent of ICD, thereby providing SMEs with access to the necessary capital to initiate and grow their businesses.

The partnership between ICD and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan is expected to have a significant impact on the SME landscape in Uzbekistan. By equipping entrepreneurs with the resources they need to succeed, this collaboration will not only support the growth of individual businesses but also contribute to the overall economic development of the country. SMEs play a crucial role in driving economic growth, creating jobs, and fostering innovation, and this partnership will help strengthen the SME ecosystem in Uzbekistan.

JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan, as a strategic partner for ICD, brings a wealth of experience and expertise to the table. As a prominent commercial bank with foreign capital, JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan has a strong track record of supporting SMEs and promoting economic development. The bank’s partnership with ICD further underscores its commitment to advancing the private sector in Uzbekistan and its dedication to supporting the country’s economic growth.

ICD, for its part, is a leading multilateral development financial institution that focuses on supporting the economic development of its member countries through the provision of finance and advisory services to private sector enterprises. By partnering with JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan, ICD is furthering its mission of promoting economic development and fostering entrepreneurship in Uzbekistan and across the Islamic world.

The LoF facility provided by ICD to JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan is just one example of the many initiatives that the two entities are undertaking to support SMEs in Uzbekistan. In addition to providing financial support, the partnership between ICD and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan will also include capacity-building initiatives and technical assistance programs to help SMEs succeed in today’s competitive business environment.

Overall, the partnership between ICD and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan represents a significant step forward in supporting SMEs and fostering economic growth in Uzbekistan. By working together, these two institutions are helping to create a more vibrant and dynamic private sector in Uzbekistan, which will ultimately benefit the country’s economy and its people. The collaboration between the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD) and JSC Ziraat Bank Uzbekistan is expected to have a far-reaching impact on the private sector in Uzbekistan.

BUSINESS & ECONOMY

In Times of Conflict, Spare a Thought for the Non-Gulf Economies

Published

2 weeks agoon

May 6, 2024By

Editor

By James Swanston

Positive news for non-GCC Arab economies has been in short supply of late. The Gaza conflict, missile attacks in the Red Sea, war in Ukraine and last month’s tit-for-tat missile strikes between Israel and Iran have weighed on sentiment, undermined limited confidence and cut into growth.

But some positives have emerged. Headline inflation rates have slowed across much of North Africa and the Levant, implying lower interest rates, a return to real growth and more stable exchange rates. March data show inflation at an annualised rate of just 0.9 percent in Morocco and 1.6 percent in Jordan. Tunisia’s inflation rate has also come down, although it is still running at over 7 percent year on year.

Egypt’s inflation rate jumped earlier this year as the government implemented price hikes to some goods and services – notably fuel. In February, the effect of the devaluation in the pound to the level of the parallel market affected prices. But March’s reading eased to an albeit still high 33 percent year on year.

Elsewhere, Lebanon’s inflation slowed to 70 percent year on year in March, the first time it has been in double – rather than triple – digits since early 2020 due to de-facto dollarisation and lower demand for imports. That said, inflation in these economies is vulnerable to increases in the prices of global foods and energy (such as oil) due to their being net importers. If supply chain disruptions persist, it could result in central banks keeping monetary policy tighter with consequences for growth and employment. And in Morocco’s case, it could undermine the Bank Al-Maghrib’s intention to widen the dirham’s trading band and formally adopt an inflation-targeting monetary framework.

The strikes by Iran and Israel undoubtedly marked a dangerous escalation in what up to now had been a proxy war. Thankfully, policymakers across the globe have for the moment worked to de-escalate the situation. Outside the countries directly involved, the most significant spillover has been the disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Many of the major global shipping companies have diverted ships away from the Red Sea due to attacks by Houthi rebels and have instead opted to go around the Cape of Good Hope.

The latest data shows that total freight traffic through the Suez Canal and Bab el-Mandeb Strait is down 60-75 percent since the onset of the hostilities in Gaza in early October. Almost all countries have seen fewer port calls. This could create fresh shortages of some goods imports, hamper production, and put upward pressure on prices.

For Egypt, inflation aside, the shipping disruptions have proven to be a major economic headache. Receipts from the Suez Canal were worth around 2.5 percent of GDP in 2023 – and that was before canal fees were hiked by 15 percent this January. Canal receipts are a major source of hard currency for Egypt and officials have said that revenues are down 40-50 percent compared to levels in early October.

The conflict is also weighing on the crucial tourism sector. Tourism accounts for 5-10 percent of GDP in the economies of North Africa and the Levant and is a critical source of hard currency inflows.

Jordan, where figures are the timeliest, show that tourist arrivals were down over 10 percent year on year between November and January. News of Iranian drones and missiles flying over Jordan imply that these numbers will, unfortunately, have fallen further.

In the case of Egypt, foreign currency revenues – from tourism and the Suez canal – represent more than 6 percent of GDP and are vulnerable. This played a large part in the decision to de-value the pound and hike interest rates aggressively in March.

The saving grace is that the conflict has galvanised geopolitical support for these economies. For Egypt, the aforementioned policy shift was accompanied by an enhanced $8bn IMF deal and, while not strictly bilateral support, the bumper Ras el-Hekma deal seems to have been accelerated as the pressure on the Egyptian economy ratcheted up. This is providing much needed foreign currency. At the same time, Jordan recently renewed its financing arrangement with the IMF for $1.2bn over four years.

Tunisia, however, is an exception. President Saied’s anti-IMF rhetoric and reluctance to pass reforms, such as harsh fiscal consolidation, in an election year, mean that the country’s staff-level agreement for an IMF deal is likely to remain in limbo. If strains on Tunisia’s foreign receipts are stretched, and the central bank and government continue with unorthodox policies of deficit financing, there is a risk that Tunisia’s economic crisis will become messier more quickly in the next year – particularly large sovereign debt repayments are due in early 2025.

James Swanston is Middle East and North Africa economist at London-based Capital Economics

BUSINESS & ECONOMY

Debt Dependency in Africa: the Drivers

Published

2 weeks agoon

May 6, 2024By

Editor

In mid-April Ghana’s efforts to restructure its sovereign debt came to nothing, increasing the risk that it couldn’t keep up with its repayments. This is a familiar story for many African countries. Twenty of them are in serious debt trouble. Carlos Lopes argues that there are three factors driving this state of affairs: the rules of the international banking system; lenders’ focus on poverty reduction rather than development needs; and unfair treatment by rating agencies.

The debt situation in many African countries has escalated again to a critical juncture. Twenty are in, or at risk of, debt distress. Three pivotal elements significantly contribute to this. Firstly, the rules governing the international banking system favour developed countries and work against the interests of African countries.

Secondly, multilateral financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank focus on poverty alleviation. This is commendable. But it doesn’t address the liquidity crisis countries face. Many don’t have the necessary readily available funds in their coffers to cover urgent development priorities due to their dependency on volatile commodity exports. As a result governments turn to raising sovereign debt under conditions that are among the most unfavourable on the planet. This perpetuates a debt dependency cycle rather than fostering sustainable economic growth.

Thirdly, there’s the significant influence of biased credit rating agencies. These unfairly penalise African countries. In turn, this impedes their ability to attract investment on favourable terms. The convergence of these three factors underscores the imperative to implement effective strategies aimed at mitigating the overwhelming debt burden afflicting African nations. These strategies must address the immediate financial challenges facing countries. They must also lay the groundwork for long-term economic sustainability and equitable development across the continent.

By tackling these issues head-on, a financial environment can be created that fosters growth, empowers local economies, and ensures that African countries have access to the resources they need to thrive.

Rules of the banking game

The Bank for International Settlements is often called the “central bank for central banks”. It sets the regulations and standards for the global banking system. But its rules disproportionately favour developed economies, leading to unfavourable conditions for African countries. For instance, capital adequacy requirements – the amount of money banks must hold in relation to their assets – and other prudential rules may be disproportionately stringent for African markets. This limits lending to stimulate economic growth in less attractive economies.

The bank’s policies also often overlook developing nations’ unique challenges. Following the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the bank introduced a new, tougher set of regulations. Their complexity and stringent requirements have inadvertently accelerated the withdrawal of international banks from Africa.

They have also made it increasingly difficult for global banks to operate profitably in African markets. As a result, many have chosen to scale back their operations, or exit. The withdrawals have reduced competition within the banking sector, limited access to credit for businesses and individuals, and hampered efforts to promote economic growth and development.

The limitations of the new regulations highlight the need for a more nuanced approach to banking regulation. The adverse effects could be mitigated by simplifying the regulations. For example, requirements could be tailored to the specific needs of African economies, and supporting local banks.

Focus on poverty alleviation

Multilateral financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank play a crucial role in providing financial assistance to many countries on the continent. But their emphasis on poverty alleviation and, more recently, climate finance often overlooks the urgent spending needs. Additionally, the liquidity squeeze facing countries further limits their capacity to prioritise essential expenditure. Wealthy nations enjoy the luxury of lenient regulatory frameworks and ample fiscal space. For their part African countries are left to fend for themselves in an environment rife with predatory lending practices and exploitative economic policies. Among these are sweetheart tax deals which often involving tax exemptions. In addition, illicit financial practices by multinational corporations drain countries of their limited resources. Research by The ONE Campaign found that financial transfers to developing nations plummeted from a peak of US$225 billion in 2014 to just US$51 billion in 2022, the latest year for which data is available. These flows are projected to diminish further.

Alarmingly, the ONE Campaign report stated that more than one in five emerging markets and developing countries allocated more resources to debt servicing in 2022 than they received in external financing. Aid donors have been touting record global aid figures. But nearly one in five aid dollars was directed towards domestic spending hosting migrants or supporting Ukraine. Aid to Africa has stagnated.

This leaves African countries looking for any opportunities to access liquidity, which makes them a prey of debt scavengers. As noted by Columbia University professor José Antonio Ocampo, the Paris Club, the oldest debt-restructuring mechanism still in operation, exclusively addresses sovereign debt owed to its 22 members, primarily OECD countries.

With these limited attempts to address a significant structural problem of pervasive indebtedness it is unfair to stigmatise Africa as if it contracted debt because of its performance or bad management.

Rating agencies

Rating agencies wield significant influence in the global financial landscape. They shape investor sentiment and determine countries’ borrowing costs. However, their assessments are often marked by bias. This is particularly evident in their treatment of African countries. African nations argue that without bias, they should receive higher ratings and lower borrowing costs. In turn this would mean brighter economic prospects as there is a positive correlation between financial development and credit ratings. However, the subjective nature of the assessment system inflates the perception of investment risk in Africa beyond the actual risk of default. This increases the cost of credit.

Some countries have contested ratings. For instance, Zambia rejected Moody’s downgrade in 2015, Namibia appealed a junk status downgrade in 2017 and Tanzania appealed against inaccurate ratings in 2018. Ghana contested ratings by Fitch and Moody’s in 2022, arguing they did not reflect the country’s risk factors. Nigeria and Kenya rejected Moody’s rating downgrades. Both cited a lack of understanding of the domestic environment by rating agencies. They asserted that their fiscal situations and debt were less dire than estimated by Moody’s.

Recent arguments from the Economic Commission for Africa and the African Peer Review Mechanism highlight deteriorating sovereign credit ratings in Africa despite some posting growth patterns above 5% for sustained periods. Their joint report identifies challenges during the rating agencies’ reviews. This includes errors in publishing ratings and commentaries and the location of analysts outside Africa to circumvent regulatory compliance, fees and tax obligations.

A recent UNDP report illuminates a staggering reality: African nations would gain a significant boost in sovereign credit financing if credit ratings were grounded more in economic fundamentals and less in subjective assessments. According to the report’s findings, African countries could access an additional US$31 billion in new financing while saving nearly US$14.2 billion in total interest costs.

These figures might seem modest in the eyes of large investment firms. But they hold immense significance for African economies. If credit ratings accurately reflected economic realities, the 13 countries studied could unlock an extra US$45 billion in funds. This is equivalent to the entire net official development assistance received by sub-Saharan Africa in 2021. These figures underscore the urgent need to address the systemic biases plaguing credit rating assessments in Africa.

Next steps

Debates about Africa’s debt crisis often lean towards solutions centered on compensation. These advocate for increased official development aid, more generous climate finance measures, or the reduction of borrowing costs through hybrid arrangements backed by international financial systems. These measures may offer temporary relief. But they need to be more genuine solutions in light of the three structural challenges facing African countries.

Carlos Lopes,a Professor at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town, is the Chair of the African Climate Foundation’s Advisory Council as well as its Chairman of the Board. He is also a board member of the World Resources Institute and Climate Works Foundation.

Courtesy: The Conversation

Red Notice: Putin is Nearby

We are not Yet Winning, but they are Losing

HLISB Introduces BizHalal To Support SMEs in the Global Halal Market

Topics

- AGRIBUSINESS & AGRICULTURE

- BUSINESS & ECONOMY

- DIGITAL ECONOMY & TECHNOLOGY

- EDITORIAL

- ENERGY

- EVENTS & ANNOUNCEMENTS

- HALAL ECONOMY

- HEALTH & EDUCATION

- IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

- INTERNATIONAL POLITICS

- ISLAMIC FINANCE & CAPITAL MARKETS

- KNOWLEDGE CENTRE, CULTURE & INTERVIEWS

- OBITUARY

- OPINION

- PROFILE

- PUBLICATIONS

- SPECIAL FEATURES/ECONOMIC FOOTPRINTS

- SPECIAL REPORTS

- SUSTAINABILITY & CLIMATE CHANGE

- THIS WEEK'S TOP STORIES

- TRENDING

- UNCATEGORIZED

- UNITED NATIONS SDGS

Trending

-

TRENDING12 months ago

TRENDING12 months agoAFRIEF Congratulates New Zamfara State Governor

-

PROFILE9 months ago

PROFILE9 months agoA Salutary Tribute to General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida: Architect of Islamic Finance in Nigeria

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoClimate Policy In Indonesia: An Unending Progress For The Future Generation

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoThe Climate Crisis is Now ‘Code Red’: We Can’t Afford to Wait Any Longer

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoIPCC report: ‘Code red’ for human driven global heating

-

HALAL ECONOMY10 months ago

HALAL ECONOMY10 months agoRevolutionizing Halal Education Through Technology

-

SPECIAL REPORTS5 months ago

SPECIAL REPORTS5 months agoRemembering Maryam Ibrahim Babangida: A Legacy of Grace, Philanthropy, and Leadership

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years agoDistributed Infrastructure: A Solution to Africa’s Urbanization