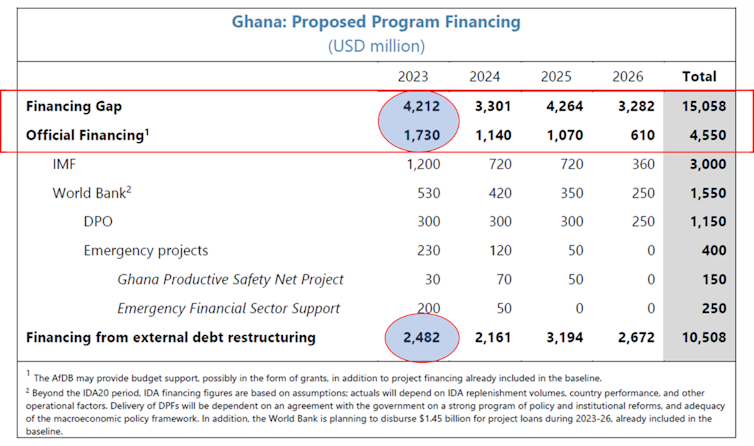

In mid-April Ghana’s efforts to restructure its sovereign debt came to nothing, increasing the risk that it couldn’t keep up with its repayments. This is a familiar story for many African countries. Twenty of them are in serious debt trouble. Carlos Lopes argues that there are three factors driving this state of affairs: the rules of the international banking system; lenders’ focus on poverty reduction rather than development needs; and unfair treatment by rating agencies.

The debt situation in many African countries has escalated again to a critical juncture. Twenty are in, or at risk of, debt distress. Three pivotal elements significantly contribute to this. Firstly, the rules governing the international banking system favour developed countries and work against the interests of African countries.

Secondly, multilateral financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank focus on poverty alleviation. This is commendable. But it doesn’t address the liquidity crisis countries face. Many don’t have the necessary readily available funds in their coffers to cover urgent development priorities due to their dependency on volatile commodity exports. As a result governments turn to raising sovereign debt under conditions that are among the most unfavourable on the planet. This perpetuates a debt dependency cycle rather than fostering sustainable economic growth.

Thirdly, there’s the significant influence of biased credit rating agencies. These unfairly penalise African countries. In turn, this impedes their ability to attract investment on favourable terms. The convergence of these three factors underscores the imperative to implement effective strategies aimed at mitigating the overwhelming debt burden afflicting African nations. These strategies must address the immediate financial challenges facing countries. They must also lay the groundwork for long-term economic sustainability and equitable development across the continent.

By tackling these issues head-on, a financial environment can be created that fosters growth, empowers local economies, and ensures that African countries have access to the resources they need to thrive.

Rules of the banking game

The Bank for International Settlements is often called the “central bank for central banks”. It sets the regulations and standards for the global banking system. But its rules disproportionately favour developed economies, leading to unfavourable conditions for African countries. For instance, capital adequacy requirements – the amount of money banks must hold in relation to their assets – and other prudential rules may be disproportionately stringent for African markets. This limits lending to stimulate economic growth in less attractive economies.

The bank’s policies also often overlook developing nations’ unique challenges. Following the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the bank introduced a new, tougher set of regulations. Their complexity and stringent requirements have inadvertently accelerated the withdrawal of international banks from Africa.

They have also made it increasingly difficult for global banks to operate profitably in African markets. As a result, many have chosen to scale back their operations, or exit. The withdrawals have reduced competition within the banking sector, limited access to credit for businesses and individuals, and hampered efforts to promote economic growth and development.

The limitations of the new regulations highlight the need for a more nuanced approach to banking regulation. The adverse effects could be mitigated by simplifying the regulations. For example, requirements could be tailored to the specific needs of African economies, and supporting local banks.

Focus on poverty alleviation

Multilateral financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank play a crucial role in providing financial assistance to many countries on the continent. But their emphasis on poverty alleviation and, more recently, climate finance often overlooks the urgent spending needs. Additionally, the liquidity squeeze facing countries further limits their capacity to prioritise essential expenditure. Wealthy nations enjoy the luxury of lenient regulatory frameworks and ample fiscal space. For their part African countries are left to fend for themselves in an environment rife with predatory lending practices and exploitative economic policies. Among these are sweetheart tax deals which often involving tax exemptions. In addition, illicit financial practices by multinational corporations drain countries of their limited resources. Research by The ONE Campaign found that financial transfers to developing nations plummeted from a peak of US$225 billion in 2014 to just US$51 billion in 2022, the latest year for which data is available. These flows are projected to diminish further.

Alarmingly, the ONE Campaign report stated that more than one in five emerging markets and developing countries allocated more resources to debt servicing in 2022 than they received in external financing. Aid donors have been touting record global aid figures. But nearly one in five aid dollars was directed towards domestic spending hosting migrants or supporting Ukraine. Aid to Africa has stagnated.

This leaves African countries looking for any opportunities to access liquidity, which makes them a prey of debt scavengers. As noted by Columbia University professor José Antonio Ocampo, the Paris Club, the oldest debt-restructuring mechanism still in operation, exclusively addresses sovereign debt owed to its 22 members, primarily OECD countries.

With these limited attempts to address a significant structural problem of pervasive indebtedness it is unfair to stigmatise Africa as if it contracted debt because of its performance or bad management.

Rating agencies

Rating agencies wield significant influence in the global financial landscape. They shape investor sentiment and determine countries’ borrowing costs. However, their assessments are often marked by bias. This is particularly evident in their treatment of African countries. African nations argue that without bias, they should receive higher ratings and lower borrowing costs. In turn this would mean brighter economic prospects as there is a positive correlation between financial development and credit ratings. However, the subjective nature of the assessment system inflates the perception of investment risk in Africa beyond the actual risk of default. This increases the cost of credit.

Some countries have contested ratings. For instance, Zambia rejected Moody’s downgrade in 2015, Namibia appealed a junk status downgrade in 2017 and Tanzania appealed against inaccurate ratings in 2018. Ghana contested ratings by Fitch and Moody’s in 2022, arguing they did not reflect the country’s risk factors. Nigeria and Kenya rejected Moody’s rating downgrades. Both cited a lack of understanding of the domestic environment by rating agencies. They asserted that their fiscal situations and debt were less dire than estimated by Moody’s.

Recent arguments from the Economic Commission for Africa and the African Peer Review Mechanism highlight deteriorating sovereign credit ratings in Africa despite some posting growth patterns above 5% for sustained periods. Their joint report identifies challenges during the rating agencies’ reviews. This includes errors in publishing ratings and commentaries and the location of analysts outside Africa to circumvent regulatory compliance, fees and tax obligations.

A recent UNDP report illuminates a staggering reality: African nations would gain a significant boost in sovereign credit financing if credit ratings were grounded more in economic fundamentals and less in subjective assessments. According to the report’s findings, African countries could access an additional US$31 billion in new financing while saving nearly US$14.2 billion in total interest costs.

These figures might seem modest in the eyes of large investment firms. But they hold immense significance for African economies. If credit ratings accurately reflected economic realities, the 13 countries studied could unlock an extra US$45 billion in funds. This is equivalent to the entire net official development assistance received by sub-Saharan Africa in 2021. These figures underscore the urgent need to address the systemic biases plaguing credit rating assessments in Africa.

Next steps

Debates about Africa’s debt crisis often lean towards solutions centered on compensation. These advocate for increased official development aid, more generous climate finance measures, or the reduction of borrowing costs through hybrid arrangements backed by international financial systems. These measures may offer temporary relief. But they need to be more genuine solutions in light of the three structural challenges facing African countries.

Carlos Lopes,a Professor at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town, is the Chair of the African Climate Foundation’s Advisory Council as well as its Chairman of the Board. He is also a board member of the World Resources Institute and Climate Works Foundation.

Courtesy: The Conversation

TRENDING12 months ago

TRENDING12 months ago

PROFILE9 months ago

PROFILE9 months ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

HALAL ECONOMY10 months ago

HALAL ECONOMY10 months ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

SPECIAL REPORTS5 months ago

SPECIAL REPORTS5 months ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago

BUSINESS & ECONOMY3 years ago